Are we really prisoners of geography? | World news

Russia’s war in Ukraine has involved many surprises. The largest, however, is that it happened at all. Last year, Russia was at peace and enmeshed in a complex global economy. Would it really sever trade ties – and threaten nuclear war – just to expand its already vast territory? Despite the many warnings, including from Vladimir Putin himself, the invasion still came as a shock.

But it wasn’t a shock to the journalist Tim Marshall. On the first page of his 2015 blockbuster book, Prisoners of Geography, Marshall invited readers to contemplate Russia’s topography. A ring of mountains and ice surrounds it. Its border with China is protected by mountain ranges, and it is separated from Iran and Turkey by the Caucusus. Between Russia and western Europe stand the Balkans, Carpathians and Alps, which form another wall. Or, they nearly do. To the north of those mountains, a flat corridor – the Great European Plain – connects Russia to its well-armed western neighbours via Ukraine and Poland. On it, you can ride a bicycle from Paris to Moscow.

You can also drive a tank. Marshall noted how this gap in Russia’s natural fortifications has repeatedly exposed it to attacks. “Putin has no choice”, Marshall concluded: “He must at least attempt to control the flatlands to the west.” When Putin did precisely that, invading a Ukraine he could no longer control by quieter means, Marshall greeted it with wearied understanding, deploring the war yet finding it unsurprising. The map “imprisons” leaders, he had written, “giving them fewer choices and less room to manoeuvre than you might think”.

There is a name for Marshall’s line of thinking: geopolitics. Although the term is often used loosely to mean “international relations”, it refers more precisely to the view that geography – mountains, land bridges, water tables – governs world affairs. Ideas, laws and culture are interesting, geopoliticians argue, but to truly understand politics you must look hard at maps. And when you do, the world reveals itself to be a zero-sum contest in which every neighbour is a potential rival, and success depends on controlling territory, as in the boardgame Risk. In its cynical view of human motives, geopolitics resembles Marxism, just with topography replacing class struggle as the engine of history.

Geopolitics also resembles Marxism in that many predicted its death in the 1990s, with the cold war’s end. The expansion of markets and eruption of new technologies promised to make geography obsolete. Who cares about controlling the strait of Malacca – or the port of Odesa – when the seas brim with containerships and information rebounds off satellites? “The world is flat,” the journalist Thomas Friedman declared in 2005. It was an apt metaphor for globalisation: goods, ideas and people sliding smoothly across borders.

Yet the world feels less flat today. As supply chains snap and global trade falters, the terrain of the planet seems more craggy than frictionless. Hostility toward globalisation, channelled by figures such as Donald Trump and Nigel Farage, was already rising before the pandemic, which boosted it. The number of border walls, about 10 at the cold war’s end, is now 74 and climbing, with the past decade as the high point of wall-building. The post-cold war hope for globalisation was a “delusion”, writes political scientist Élisabeth Vallet, and we’re now seeing the “reterritorialisation of the world”.

Facing a newly hostile environment, leaders are pulling old strategy guides off the shelf. “Geopolitics are back, and back with a vengeance, after this holiday from history we took in the so-called post-cold war period,” US national security adviser HR McMaster warned in 2017. This outlook openly guides Russian thinking, with Putin citing “geopolitical realities” in explaining his Ukraine invasion. Elsewhere, as faith in an open, trade-based international system falters, map-reading pundits such as Marshall, Robert Kaplan, Ian Morris, George Friedman and Peter Zeihan are advancing on to bestseller lists.

Hearing the mapmongers ply their trade, you wonder if anything has changed since the 13th-century world of Genghis Khan, where strategy was a matter of open steppes and mountain barriers. Geopolitical thinking is unabashedly grim, and it regards hopes for peace, justice and rights with scepticism. The question, however, is not whether it’s bleak, but whether it’s right. Past decades have brought major technological, intellectual and institutional changes. But are we still, as Marshall contends, “prisoners of geography”?

In the long run, we are creatures of our environments to an almost embarrassing degree, flourishing where circumstances permit and dying where they don’t. “If you look at a map of the tectonic plate boundaries grinding against each other and superimpose the locations of the world’s major ancient civilisations, an astonishingly close relationship reveals itself,” writes Lewis Dartnell in his splendid book, Origins. The relationship is no accident. Plate collisions create mountain ranges and the great rivers that carry their sediment down to the lowlands, enriching the soil. Ancient Greece, Egypt, Persia, Assyria, the Indus valley, Mesoamerica and Rome were all near plate edges. The Fertile Crescent – the rich agricultural zone stretching from Egypt to Iran, where farming, writing and the wheel first emerged – lies over the intersection of three plates.

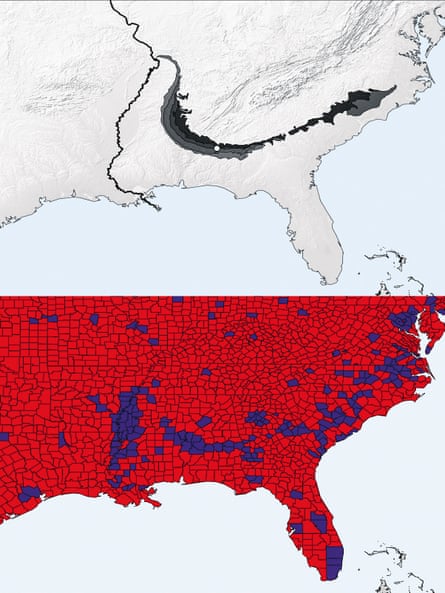

Geography’s effects can be impressively enduring, as voting patterns in the southern US show. The deep south is heavily Republican, but an arc of Democratic counties curves through it. That dissenting band makes a shape “instantly recognisable to a geologist”, writes scientist Steven Dutch. It matches an outcrop of sediment from tens of millions of years ago, deposited during the hot Cretaceous period when much of the present-day US was underwater. With time, the deposits were compressed into shale, and with more time, after the waters had receded, they were exposed by erosion. In the 19th century, Dutch explains, planters recognised the outcropping – called the “Black Belt” for its rich, dark soil – as ideal for cotton. To pick it, planters brought enslaved people, whose descendants still live in the area and regularly oppose conservative politicians. The city of Montgomery, Alabama –“smack in the middle” of the Cretaceous band, Dartnell notes – was also a centre of the civil rights movement, where Martin Luther King Jr. preached and Rosa Parks sparked the bus boycott.

Geopoliticians, of course, care more about international wars than local elections. In this, they hark back to Halford Mackinder, an English strategist who essentially founded their way of thinking. In a 1904 paper, The Geographical Pivot of History, Mackinder gazed at a relief map of the world and posited that history could be seen as a centuries-long struggle between the nomadic peoples of Eurasia’s plains and the seafaring ones of its coasts. Britain and its peers had thrived as oceanic powers, but, now that all viable colonies were claimed, that route was closed and future expansion would involve land conflicts. The vast plain in the “heart-land” of Eurasia, Mackinder felt, would be the centre of the world’s wars.

Mackinder wasn’t wholly correct, but his predictions’ broad contours – clashes over eastern Europe, the waning of British sea power, the rise of the land powers Germany and Russia – were right enough. Beyond the details, Mackinder’s vision of imperialists running out of colonies to claim and turning on one another was prophetic. When they did, he foresaw, Eurasia’s interior would be the prize. The Heartland “offers all the prerequisites of ultimate dominance of the world”, he later wrote. “Who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island; who rules the World-Island commands the world.”

Mackinder meant that as a warning. But the German army general Karl Haushofer, believing Mackinder to possess “the greatest of all geographical worldviews”, took it as advice. Haushofer incorporated Mackinder’s insights into the emerging field of Geopolitik (from which we get the English “geopolitics”) and passed his ideas on to Adolf Hitler and Rudolf Hess in the 1920s. “The German people are imprisoned within an impossible territorial area,” Hitler concluded. To survive they must “become a world power”, and to do that they must turn east – to Mackinder’s Heartland.

Adolf Hitler’s conviction that Germany’s fate lay in the east was a far cry from Steven Dutch’s observation that Cretaceous rocks predict votes. Yet informing both is the theory that what’s beneath our feet shapes what’s in our heads. By the second world war, when armies clashing over strategically valuable territory had ripped up much of Eurasia, that seemed hard to deny. Mackinder, who lived through that war, saw little reason to believe geography’s “obstinate facts” would ever give way.

Halford Mackinder insisted that the relief map still mattered, but not everyone agreed. Throughout the 20th century, idealists searched for ways to make international relations something other than a “perpetual prize-fight”, as the British economist John Maynard Keynes put it. For Keynes and his followers, trade might accomplish this. If countries could rely on open commerce, they’d no longer have to seize territory to secure resources. For other idealists, new air-age technologies were the key. With all places linked to all others via the skies, they hoped, countries would stop squabbling over strategic spots on the map.

These were hopes, though, not yet realities. The cold war, which divided the planet into trade blocs and military alliances, kept leaders’ eyes fixed on maps. Children learned to read maps, too, thanks to the 1957 French board game La Conquête du Monde – the conquest of the world – that the US firm Parker Brothers sold widely under the name Risk. It had a 19th-century ambience, with cavalries and antiquated artillery pieces, but given that superpowers were still carving up the map, it was also uncomfortably relevant.

Geopolitical thought, though muted since its association with the Nazis, nevertheless left its marks on the cold war. The US’s key strategist, George F Kennan, downplayed the conflict’s ideological component. Marxism was a “fig leaf”, he insisted. The true explanation for Soviet conduct was the “traditional and instinctive Russian sense of insecurity” engendered by centuries “trying to live on a vast exposed plain in the neighbourhood of fierce nomadic peoples”. To this Mackinder-tinged problem, Kennan proposed a Mackinder-tinged solution: “containment”, which sought not to eradicate communism, but to hem it in. This campaign ultimately entailed US intervention all over the world, including sending 2.7 million service members to fight the Vietnam war. For many who served, that unsuccessful war was a “quagmire” – a ground that sucks you in. Not until the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 did it seem like geography might finally lose its grip.

The cold war had divided the world economically, and its end brought trade walls tumbling down. The 90s saw a frenzy of trade agreements and institution-building: the European Union, the North American Free Trade Agreement (Nafta), Mercosur in Latin America and, towering above all, the World Trade Organization. The number of regional trade agreements more than quadrupled between 1988 and 2008, and they deepened as well, involving more thoroughgoing coordination. In that period, trade tripled, rising from less than a sixth of global GDP to more than a quarter.

The more countries could secure vital resources by trade, the less reason they’d have to seize land. Optimists like Thomas Friedman believed countries that were tightly woven into an economic network would forgo starting wars, for fear of losing access to the humming network. Friedman lightheartedly expressed this in 1996 as the Golden Arches Theory of Conflict Prevention: no two countries with McDonald’s will go to war with each other. And he wasn’t far off. Although there have been a handful of conflicts between McDonald’s-having countries, an individual’s chance of dying in a war between states has diminished remarkably since the cold war.

At the same time as trade was diminishing the likelihood of war, military technologies changed its shape. Just months after the Berlin Wall fell, Saddam Hussein led an Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. This was an old-school geopolitical affair: Iraq had amassed the world’s fourth-largest army, and by seizing Kuwait it would control two-fifths of the world’s oil reserves. What is more, its formidable ground forces were shielded by a large, trackless desert that was nearly impossible to navigate. Mackinder would have appreciated the strategy.

But the 90s were no longer the age of Mackinder. Saddam discovered this when a US-led coalition sent bombers from Louisiana, England, Spain, Saudi Arabia and the island of Diego Garcia to drop their payloads over Iraq, disabling much of its infrastructure within hours. More than a month of airstrikes followed, and then coalition forces used the new satellite technology of GPS to swiftly cross the desert that Iraqis had mistaken for an impenetrable barrier. A hundred hours of ground fighting were enough to defeat Iraq’s battered army, though high-ranking Iraqi officers observed afterward even this hadn’t been necessary. A few more weeks of the punishing airstrikes, and Iraq would have withdrawn its troops from Kuwait without having ever faced an adversary on the battlefield.

What even was the “battlefield” by the 90s? The Gulf war portended a much-discussed “revolution in military affairs”, one that promised to replace armoured divisions, heavy artillery and large infantries with precision airstrikes. The Russian military theorist Vladimir Slipchenko noted that strategists’ familiar spatial concepts such as fields, fronts, rears and flanks were losing relevance. With satellites, planes, GPS and now drones, “battlespace” – as strategists today call it – isn’t the wrinkled surface of the Earth, but a flat sheet of graph paper.

A sky full of drones hasn’t meant world peace. But champions of the new technologies have at least promised cleaner fighting, with fewer civilians killed, captives taken and troops dispatched. The revolution in military affairs allows powerful countries – mainly the US and its allies – to target individuals and networks rather than whole countries. This seemed to mark a shift from international war toward global policing, and from blood-soaked disruptions of geopolitics toward the smoother, though still sometimes lethal, operation of globalisation.

But has globalisation actually replaced geopolitics? “The 90s saw the map reduced to two dimensions because of air power,” concedes geostrategist Robert Kaplan. Yet the “three-dimensional map” was restored “in the mountains of Afghanistan and in the treacherous alleyways of Iraq”, he writes. The contrast between the 1991 Gulf war and the 2003–11 Iraq war is telling. In both, the global superpower led a coalition against Saddam’s Iraq. Yet the first saw air power used to achieve a brisk victory, whereas the second looked, to the untrained eye, like another US-made quagmire.

Global exports, which had been growing rapidly since the 90s, plateaued around 2008. Today “deglobalisation” – a substantial retreat of trade – is plausible in the near future, and European integration has faced an enormous setback with Brexit. As if on cue, there is now also a land war in Europe. Indeed, it is a “McDonald’s war” – the fast-food chain had hundreds of locations in Russia and Ukraine. Whatever economic benefits Russia reaped from peaceful commerce were presumably outweighed, in Putin’s mind, by Ukraine’s warm-water ports, natural resources and strategic buffer to Russia’s vulnerable west. This is, as Kaplan has memorably put it, the “revenge of geography”.

With the revenge of geography has come the return of geopolitical theorists, often associated with the self-described “private global-intelligence firm” Stratfor. The “shadow CIA”, as the magazine Barron’s called it, has fed off the failures of post-cold war idealism. Many of the recent maps-explain-history bestsellers have emerged from its milieu. Robert Kaplan was for a time its chief geopolitical analyst. Ian Morris, author of this year’s Geography is Destiny, has served on its board of contributors. And geopolitical authors George Friedman and Peter Zeihan were the firm’s founder and vice-president, respectively. (The British writer Tim Marshall has a different network; his Prisoners of Geography boasts a foreword by a former MI6 chief.)

In 2014, the public gained some insight into Stratfor’s work via 5m of the firm’s emails that hackers posted to WikiLeaks. This firm, it turned out, hadn’t limited itself to cartographic pontification. It had entered the fray, and seemed to have a decidedly cosy relationship to power. Stratfor, hackers revealed, had been monitoring activists on behalf of corporations, at one point proposing to investigate journalist Glenn Greenwald for the Bank of America. Among the company’s subscribers and clients were Dow Chemical, Raytheon, Goldman Sachs, Merrill Lynch, Bechtel, Coca-Cola and the US Marine Corps. It’s unclear if Stratfor, which was bought out by another intelligence firm in 2020, amounts to anything more than mid-size fish in the vast sea of the US security apparatus. But the leaked emails did include intelligence sourced directly from Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu about the Iranian nuclear programme, Israel’s willingness to assassinate a Hezbollah leader, and its prime minister’s feelings about his counterpart in Washington (“BB dislikes Obama immensely”).

It sold secrets, but ultimately Stratfor’s clientele depended on it for predictions. Geopoliticians haven’t been shy about making these. Indeed, of late they have offered so many cross-cutting forecasts that one starts to doubt the cast-iron confidence with which they are issued. Will Turkey become the “pivot point” for Europe, Asia and Africa, as Stratfor founder George Friedman contends? Or perhaps India will become the “global pivot state”, as Kaplan believes (adding that Iran is the “most pivotal geography” of the Middle East, Taiwan is “pivotal to” maritime Asia and North Korea is the “true pivot of east Asia”).

It would be easier to take such talk seriously if the geopoliticians had a proven record. But we are still waiting for “the coming war with Japan” that George Friedman wrote a book about in 1991, and any assessment of Kaplan’s forecasting must note his support of the Iraq war, including joining a secret committee advocating the war to the White House. To his credit, Kaplan has admitted his errors. “When I and others supported a war to liberate Iraq,” he has written, “we never fully or accurately contemplated the price.”

Whether the modern Mackinders are fully or accurately contemplating all relevant factors now will take decades to discover. But their outlook on the present is legible enough. It’s largely a scoffing conservatism, one that doubts whether is much new under the sun. For Marshall, the “tribes” of the Balkans are perpetually in the thrall of “ancient suspicions”, the Democratic Republic of the Congo “remains a place shrouded in the darkness of war” and the Greeks and Turks have been locked in a “mutual antagonism” since the Trojan war. Kaplan sees things similarly. Russia has always been an “insecure and sprawling land power”, he writes, its people held “throughout history” in “fear and awe” of the Caucasus mountains. He approvingly quotes a retired historian’s theory that Russians, facing cold winters, possess an enhanced “capacity for suffering”.

The academic geographer Harm de Blij, reviewing Kaplan’s The Revenge of Geography, found the book at times “excruciating” and wrote that scholars would be surprised to see crude environmental determinism, “long consigned to the dustbin”, given new life. Kaplan concedes that thinking geopolitically requires reclaiming “decidedly unfashionable thinkers” such as Mackinder, who have been tainted by their connections to imperialism and nazism. The “misuse of his ideas”, however, doesn’t mean Mackinder was wrong, Kaplan insists. And so we’re back to the endlessly insecure Russians, cowering in fear and awe of a mountain range.

Even powerful leaders, according to the geopoliticians, can do little to defy the map. After protests ousted the Russia-friendly Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych in 2014, Putin “had to annex Crimea”, Marshall writes. Though Marshall condemns Russian aggression, his tone is similar to the one Putin uses to justify it. “They are constantly trying to sweep us into a corner,” Putin said of Russia’s rivals in 2014. “If you compress the spring all the way to its limit, it will snap back hard.” One might object that Putin’s ideas and attitudes, not his map, are driving Russian belligerence, yet geopolitics makes little room for such factors. “All that can be done,” writes Marshall in another context, “is to react to the realities of nature.”

At the heart of the geopolitical worldview is an appreciation of the constraints posed by “geography’s immutable nature”, as former Stratfor vice-president Zeihan writes. Redraw a few border lines and “the map that Ivan the Terrible confronted is the same one Vladimir Putin is faced with to this day”, Marshall explains. As neither the map nor the calculations around it change much, wise action mainly involves accepting intransigent facts. “There was, is and always will be trouble in Xinjiang,” a resigned Marshall writes, in what could be the catchphrase of the entire movement.

“Geography is unfair,” Ian Morris writes, and if “geography is destiny”, as he also contends, then this is a recipe for a world in which the strong remain strong and the weak remain weak. Geopoliticians excel at explaining why things won’t change. They’re less adept at explaining how things do.

That may explain geopoliticians’ notable blitheness concerning history. Did German unification come because “the Germanic states finally became tired of fighting each other”, as Marshall writes? Were the Vietnam and Iraq wars “merely isolated episodes in US history, of little lasting importance”, as Stratfor founder Friedman posits? Is it true, as Zeihan contends, that, “unlike everyone else in Europe, the English never needed to worry about an army getting bored and leisurely passing through”? Or, as Kaplan insists, that “America is fated to lead”? The geopoliticians’ historical accounts fall somewhere between “pleasantly breezy” and “harried guide rushing the schoolchildren through the castle before the next tour bus arrives”.

It is important to note that this isn’t how actual geographers – the ones who produce maps and peer-reviewed research – write. Like geopolitical theorists, geographers believe in the power of place, but they have long insisted that places are historically shaped. Law, culture and economics produce landscapes as much as tectonic plates do. And those landscapes change with time.

Even topography, geographers note, isn’t as immutable as geopoliticians suppose. Zeihan, a vice-president at Stratfor for 12 years (“You can only speak at Langley so many times”, he sighs in a recent book), has long insisted that the outsize power of the US can be attributed to its “perfect Geography of Success”. Settlers arrived in New England, encountered substandard agricultural conditions where “wheat was a hard no”, and were fortunately spurred on to claim better lands to the west. With those abundant farmlands came “the real deal”: an extensive river system allowing internal trade at a “laughably low” cost. These features, Zeihan writes, have made the US “the most powerful country in history” and will keep it so for generations. “Americans. Cannot. Mess. This. Up.”

But such factors aren’t constants. Wheat was once commonly grown in New England, despite Zeihan’s insistence that it was a “hard no” there. It was historical events – the arrival of pests such as the hessian fly (believed to have travelled with German troops fighting in the Revolutionary war) and the exhaustion of the soil by destructive farming practices – that decreased its grain outputs. The natural rivers that Zeihan makes so much of were also variables. To work, they had to be supplemented with an expensive, artificial canal system, and then within decades they were superseded by new technologies. Today, more US freight, by value, travels via rail, air and even pipeline than via water. Trucks haul 45 times as much value as boats or ships do.

Which is another way of saying that we don’t always accept the topographies we inherit. The world’s tallest skyscraper, the Burj Khalifa, sprouts from Dubai, which was for centuries an unpromising fishing village surrounded by desert and salt flats. Little about its relief map destined it for greatness. Its climate is sweltering and oil sales, though once substantial, now account for less than 1{6d6906d986cb38e604952ede6d65f3d49470e23f1a526661621333fa74363c48} of the emirate’s economy. If there’s something distinctive about Dubai, it is its legal landscape, not its physical one. The emirate isn’t governed by a single lawbook but is chopped up into free zones – Dubai Internet City, Dubai Knowledge Park and International Humanitarian City among them – designed to attract various foreign interests. The Dubai desert is essentially “a huge circuit board”, the urban theorist Mike Davis once wrote, to which global capital can easily connect.

Turning Dubai into a business hub has meant physically remaking it in ways that defy any notion that the map is destiny. Much of Dubai’s bustling commerce passes through the Port of Jebel Ali, the largest in the Middle East. Having an enormous deep port would seem to be an important piece of geographic luck, until you realise that Dubai carved it, at great expense, out of the desert. With dredged sand, Dubai engineers have also manufactured islands, including an archipelago of more than 100 arranged as a world map. Green parks and indoor ski slopes complete the nature-defying spectacle.

Terraforming Dubai is, unfortunately, the least of what we can do. Global warming is scrambling the landscape, threatening to drown islands, make deserts of grasslands and turn rivers to dust. It’s bizarre how little geopolitical treatises make of this. “Any reader will have noticed that I do not deal with the question,” admits Friedman at the end of his book The Next 100 Years. Save for minor comments and asides, the same could be said of Morris’s Geography Is Destiny, Marshall’s Prisoners of Geography, Kaplan’s The Revenge of Geography and Zeihan’s The Accidental Superpower.

Geopoliticians’ reluctance to reckon with the climate crisis comes from their sense that there are only two options: transcend the landscape or live with it. Either globalisation will release us from physical constraints or we’ll remain trapped by them. And since new technologies and institutions clearly haven’t eradicated the importance of place, we must revert to geopolitics.

But are these the only options? It seems much more likely that the unravelling of globalisation won’t pitch us backward into the 19th century, but into a future full of unprecedented hazards. We’ll experience environmental constraints profoundly in that future, just not in the way geopoliticians predict. Rather, it’s the human-made landscape, not the natural one, that will shape our actions – including the ways that we’ve remade the physical environment. Geography isn’t “unchanging”, as Kaplan writes, but volatile. And where we’re going, the old maps won’t help.