Call for Pikes Peak to be renamed to its Ute name gains steam | Subscriber-Only Content

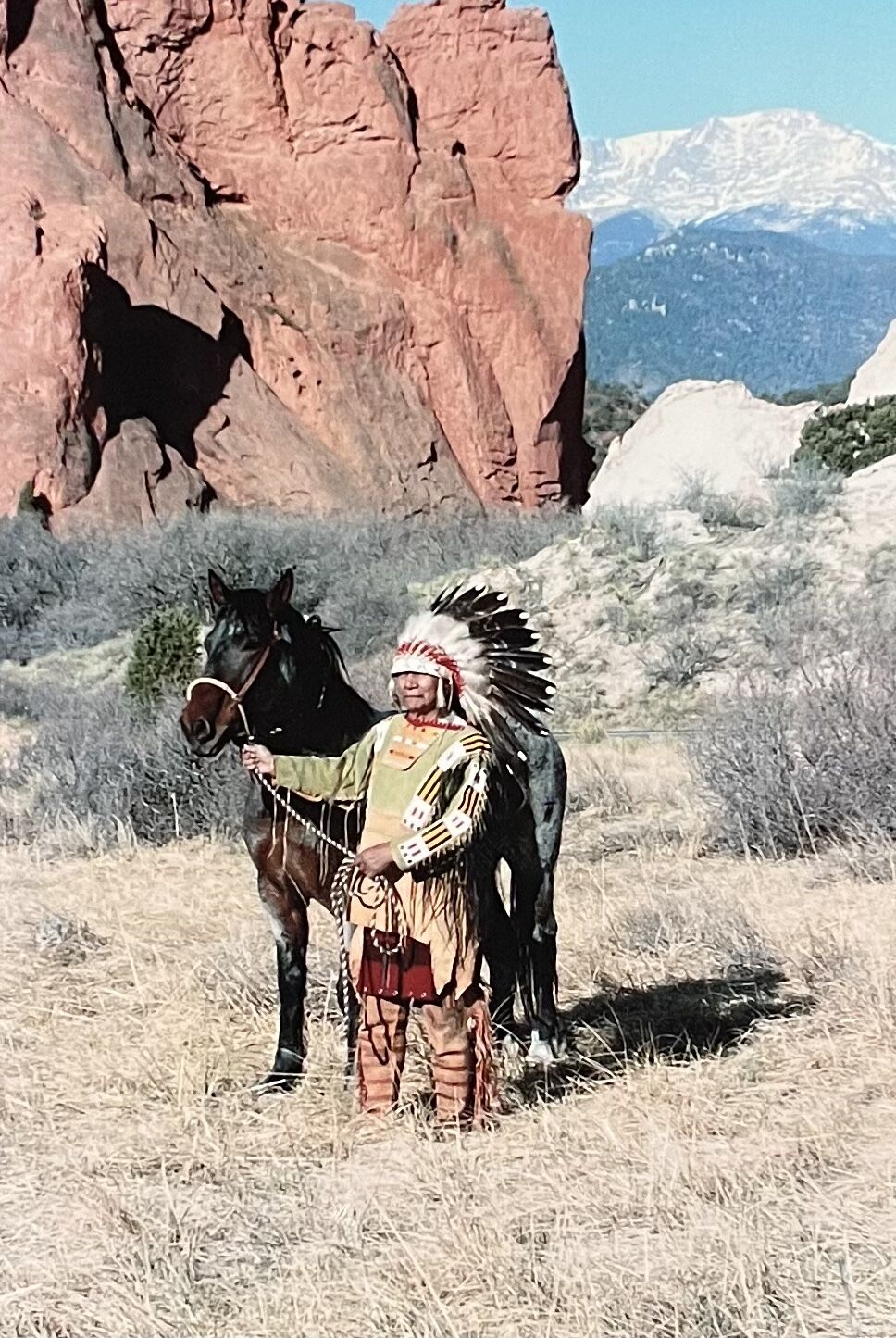

Austin Box, a Southern Ute tribal elder, knows the story well.

“When they were camped here, rather than the sun coming down on the lower area, it went up to Pikes Peak first and showed the sunlight there,” he says in a slow, easy cadence.

“When the tribe looked up, they saw the sunlight. The sun wasn’t shining on the lower area. That’s why they named it Sun Mountain. Tavá Kaa-vi.”

The 91-year-old Pikes Peak region resident and member of the Ignacio-based Southern Ute Indian Tribe sometimes refers to Pikes Peak by its Ute name — especially when he’s speaking about his cultural heritage.

Southern Ute Tribal Elder Austin Box, who lives in the Pikes Peak region, says he’s neutral on the idea of changing the name of Pikes Peak to Tavá Mountain.

Some people want that to be the case all the time.

A grassroots movement to rename the 14er known for 132 years as Pikes Peak to Tavá Mountain has been brewing for years, but with recent successes other communities have had in returning American mountains to a moniker that speaks of their roots, optimism is high.

Colorado College professor Sarah Hautzinger, a cultural and political anthropologist, raises the idea whenever she can.

In 2015, when the nation’s tallest mountain, Mount McKinley, was reclaimed as Denali, its name in the indigenous Athabascan language, Hautzinger remembers thinking, “that could never happen with Pikes Peak because there are too many things branded around Pikes Peak.”

A dusting of fresh snow covers Pikes Peak and Garden of the Gods. A movement to change the name of Pikes Peak has gained traction.

Today, she says, “We’re in a different moment.”

Pikes Peak

Should Pikes Peak, named after white Army officer Zebulon Pike, be renamed Tavá Mountain – its Ute name?

You voted:

Eradicating derogatory names and other words that don’t fit the times has become a nationwide movement.

A new Colorado law banning American Indian school mascots is set to take effect June 1. A federal district court judge in December denied an injunction a group of Native Americans sought in claiming the legislation is discriminatory.

Also last month, a federal panel approved renaming Squaw Mountain, 30 miles west of Denver, to reflect an early 19th century Cheyenne woman who negotiated agreements among white settlers, traders and soldiers and Indian tribes in Colorado. It’s now Mestaa’ehehe (mess-taw-HAY) Mountain.

Before Pikes Peak was Pikes Peak, Ute Indians called it Tavá Mountain, which means Sun Mountain, because the sun would first appear on top of the mountain before making its way to the lower regions, which it still does today.

While “Pikes Peak” in itself does not denote racism, the fact that Colorado Springs’ most recognized attraction was named after a white Army officer, Zebulon Montgomery Pike, who neither reached the top nor knew it would bear his name, is enough for supporters to call for change.

“There is no real compelling reason the mountain should be named after Zebulon Pike,” says John Harner, who teaches geology and environmental studies at the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs.

“He never summited the mountain, he grossly overestimated its height, and he spent no real time in the region or made any lasting impacts here,” Harner said.

Alternatively, he said, the Utes lived in the region for a long time and actively used resources on the mountain.

“Tavá remains a sacred mountain to the Utes,” Harner said, adding that Sun Mountain seems a more appropriate reference.

At one time, seven bands of the Ute tribe covered the state, Box said, enjoying the mineral waters of Manitou Springs and finding shelter and meaning in Garden of the Gods.

“Colorado is our home,” Box said proudly. “We’re the only indigenous tribe to Colorado.”

Tavá speaks of the beauty of the natural landscape and the mountain itself, Hautzinger argues, which carries power and meaning beyond a militiaman’s surname.

“The Tabeguache Ute were the Ute of Tavá,” she said, or the People of Sun Mountain.

Andrew Irvine and Jessica Hawkins stand on the stone border of the Grandview Overlook in Palmer Park in February to get a better view of 14,115-foot Pikes Peak and downtown Colorado Springs as clouds begin to build over the mountain. Changes in laws regarding American Indian heritage, along with a recent name change of another Colorado mountain to an American Indian name, has helped give momentum to a movement to change Pikes Peak’s name.

Pike called it ‘Grand’

Another point, Harner said, is that Pike’s mission to the region remains “somewhat controversial.”

Pike was ordered to lead two exploratory expeditions into the unchartered West, the first to the Mississippi River, the second to the Arkansas River, when Pike became among the first European-Americans to set eyes on Pikes Peak.

He did what no other 19th-century adventurer before him had: Pike kept a detailed journal of his trips.

He and his men, whom he referred to as “damned rascals,” being long on courage and short on character, attempted to climb what became known as Pikes Peak in November 1806 but were unprepared.

The group wore thin cotton uniforms and encountered waist-deep snow and frostbite. Near starvation, they turned around.

“No man can scale its summit, and no man ever will,” Pike wrote in his journal.

Pike appeared to be somewhat of a dullard, Harner said.

“He was unsure of exactly where he was, misidentifying rivers and other features, and ended up captured by Spanish forces in the San Luis Valley,” he said.

Spaniards released Pike and his men to American territory in July 1807.

Pike died at age 34, shortly after attaining the title of brigadier general and while leading an attack on British troops in the War of 1812.

In journal entries, Pike called the mountain “the Grand Peak” and “Highest Peak.”

Explorers, trappers and settlers referred to it as “Pike’s Highest Peak,” but some called it “James Peak,” in honor of botanist Edwin James, who on July 14, 1820, became the first known person to ascend to the top of the mountain.

James wrote the area was “wholly unfit for cultivation and of course uninhabitable by a people dependent on agriculture.”

Others maintained the Spanish name of El Capitàn. Arapahoe people called the mountain a name that means clouds.

Newspapers dubbed the mountain “Pike’s Peak” during Colorado’s gold rush of 1859, according to historical accounts. The federal government made it official in 1890 — minus the apostrophe, as was the custom of the nation’s Board on Geographic Names.

‘Known worldwide as Pikes Peak’

Public buy-in of renaming “America’s mountain” — today’s subtitle for Pikes Peak — could be tough.

Unlike Squaw Mountain, Pikes Peak is not considered derogatory, said Susan Davies, executive director of the Trails and Open Space Coalition, which supports local lands.

“I’ve really respected this process of renaming peaks that are offensive, but Pike isn’t offensive — he didn’t do anything that made people angry — so it doesn’t fit that category,” she said.

Davies said she’d like to survey her organization’s 1,000 members and 5,000 newsletter recipients, who focus on preserving the area’s parks, trails and open spaces, to find out their views.

“I think it’s very interesting,” she said of the topic. “I also think it’s very sensitive. Some people would be really opposed to it and other people would be really excited. It’d be hard to please everybody. But it’s worth a conversation.”

Johnna Reeder Kleymeyer, president and CEO of the Colorado Springs Chamber & Economic Development Corporation, agrees.

“Honoring our region’s history and people through the names of landmarks is important,” she said via email. “Renaming such a prominent part of our region warrants communitywide conversation.”

Because beyond the politics, there’s this consideration, notes Harner, author of the book, “Profiting from the Peak.” His book surveys the events and socioeconomic conditions that formed Colorado Springs and contributed to today’s urban layout, personality and cultural values.

“A core component of our city’s identity is from our relationship with Pikes Peak,” Harner said. “You cannot think of the city without thinking of the mountain.

“Of course, changing a name like this would create great controversy.”

The name’s significance to the region is as vast as the mountain itself.

Under city founder Gen. William Jackson Palmer, Pikes Peak Avenue was intended to be Colorado Springs’ “main street” that “would line up with the majestic view of the mountain that dominates the landscape,” according to the 2016 Experience Downtown Colorado Springs master plan completed by the city and the Downtown Development Authority.

As she sat on the pinnacle of Pikes Peak in 1893, English college professor Katharine Lee Bates was inspired to write a poem that became the lyrics to the patriotic song, “America the Beautiful.”

Many local businesses incorporate the name Pikes Peak, as do longstanding events, such as the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb, the Pikes Peak Marathon and the Pikes Peak or Bust Rodeo.

Merry Jo Larsen, who owns the Cowhand, a Western apparel and gift store in Woodland Park for three generations, attended a dedication ceremony in the late 1990s for a sign that says “TAVA, Mountain of the Sun.”

The sign, which overlooks Pikes Peak in the town’s Bergstrom Park, was part of American Discovery Trail Art Project, and Utes were there to bless the community’s recognition.

But Larsen opposes any proposal to change the name.

“It’s known worldwide as Pikes Peak,” she said. “It’d be like changing the name of Washington, D.C. It would confuse people. They wouldn’t know what it was.”

Larsen said she grew up at a time when Utes populated the area, and she values their history.

She’d rather see more cultural events and educational programs about ancestral and contemporary Native Americans.

“Just changing the name wouldn’t do a thing for anybody,” Larsen said.

‘Good to have both names’

Austin Box says he’s neutral on the issue — the name Pikes Peak doesn’t bother him.

Both camps of thought possibly could be satisfied with an idea from Karen Box Anderson, one of Box’s daughters who is an artist in the Pikes Peak region.

As the product of a Northern Ute mother and a Southern Ute father, she’s grown up in two worlds — the white and the Indian.

“To me, this is just people that are wanting to change the name because they feel guilty of the past,” Anderson said.

She doesn’t agree with dropping the name Pikes Peak and completely switching to Tavá Mountain.

“If they’re thinking of it as being an honor to the Ute people, I’m sure it is, but no one’s going to be able to pronounce it correctly,” she said.

It’s pronounced Tuh-VAH, not Ta-vaa, as most people say it.

Why not leave Pikes Peak and add Tavá Mountain afterward — along the lines of companies having a main name and a “doing business as” name.

“I think it would be good to have both names, the English word, where you know the origination, and then the Ute word of the mountain,” Anderson said. “Then, you’re appeasing both sides of the issue.”

David Armstrong, whose family namesake is on a building at Colorado College, likes the concept of acknowledging the mountain’s Native American tradition as well as its European-American influences.

“Why can’t it have two names — the region and identity,” he said. “There’s space for both cultures here; it’s only that one has been largely ignored for a long time.”

Armstrong’s grandfather, Willis Armstrong, was a football legend at Colorado College at the end of the 19th century, and after graduating in 1899 went on to help found Colorado Springs National Bank.

Adjacent to Armstrong Hall, Colorado College’s main quad was informally called Armstrong Quad until 2019, when as part of an anti-racist initiative, officials renamed it Tavá Quad in a ceremony that included a Ute blessing and dance performance.

“I’m convinced my grandfather would be pleased to know about the naming,” Armstrong said.

His great-grandfather, David Heizer, came to Colorado Springs after the Civil War ended in 1865 and was the community’s leader when a Ute delegation rode down Ute Pass for a meeting that led to the settlement of Colorado Springs.

“I think he also had a real appreciation for the Native American culture,” Armstrong said.

Over the years, Austin Box has been called on to consult on such projects as retooling Garden of the Gods Park and attend functions. Humor, he said, gets him through.

At a celebration marking the 200th anniversary of Pike’s “discovery,” Box met a man dressed like Zebulon Pike.

“I was dressed in my Indian outfit,” Box said.

A woman said she wanted to take a photo and told them to smile. Box instead pointed at the man dressed as Pike.

“After she developed the pictures, she asked me why I did that,” Box said. “I was telling this guy next to me to go back to where you come from.”