Do You Understand the Place? — Landscaping Twin Peaks

Landscapes are key to understanding our body-minds and by extension our Twin Peaks. The show employs familiar landforms that deeply resonate with our collective unconscious, and whose “coordinates” direct important events in the series. For example, clues lead Cooper to Owl Cave—a chamber protecting “coordinates” to a circular pit surrounded by trees deep in the heart of Glastonbury Grove. Other coordinates lead to another pit marked by a single sycamore tree—an extraction point to the Fireman’s Fortress. Others lead to a deadly boulder—a target for the arrow of an entire plotline.

It turns out archetypal and real-life doppelgängers of these landforms direct the events of major religions as well. Let’s spelunk into each one.

Caves

Caves, with their shadowy twilight zones, are a great place to start any mythic journey as they are womb-like and occupy a very, very, very special place in the American religious imagination. Jesus was born in a cave and resurrected in one; Elijah spoke to his creator outside a cave on Mount Carmel; St. Francis of Assisi meditated naked in Eremo della Carceri; Saint John received his epic dream vision in the Cave of the Apocalypse on Patmos Island; Muhammed met his creator inside the Cave of Hira; Joseph Smith received the plates that would become the Book of Mormon near the Cave of Chomora, and then hid them there, “along with other sacred treasures” like the Sword of Laban; Bodhidharma, after igniting Zen Buddhism and all martial arts at Shaolin Temple, meditated inside a nearby cave for so long (nine years) that his arms and legs fell off and his eyes dried out! Commemorative eyeless dolls in Japan called Daruma look like black, white, and red eggs. It’s customary to color in one of the empty eyes as a form of good luck magic, and then burn the doll every new year.

People pilgrimage to Bodhidharma’s cave and to the others. We’d go to Owl Cave if we could! Lynch/Frost filmed some of the Owl Cave scenes at Bronson Cave in Los Angeles, itself a movie star of sorts, and they also used sets—the cave lifted up out of the “real” and into the abstract.

COOPER: Where is the symbol?

HAWK: This way.

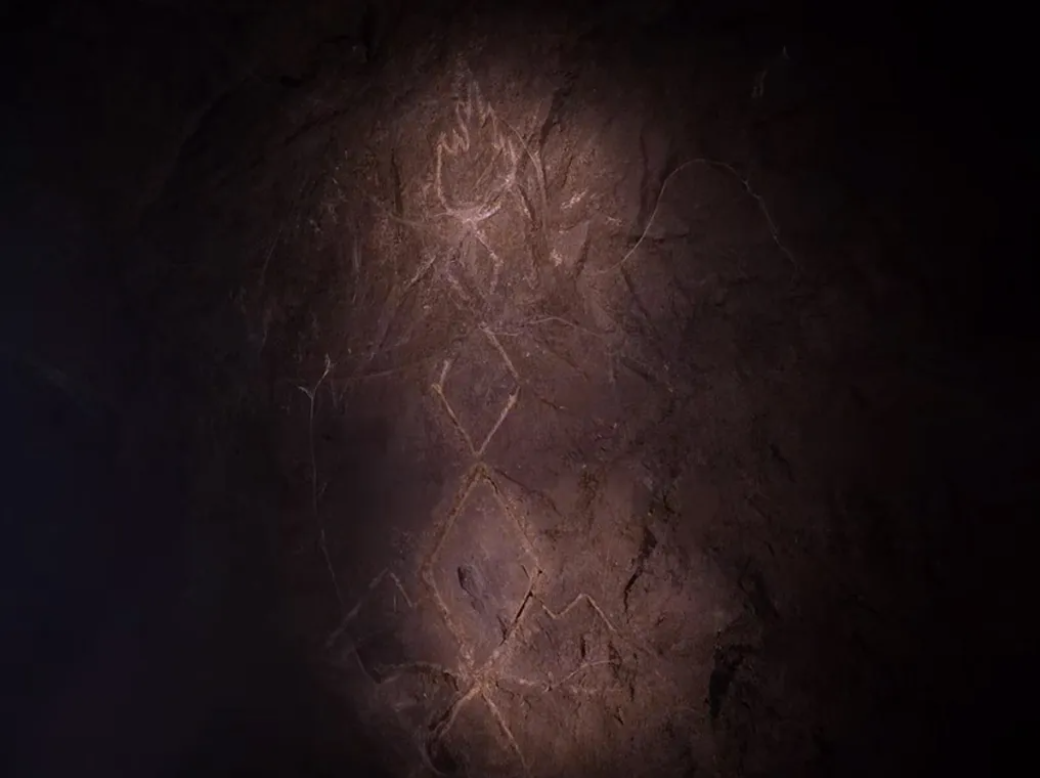

Here are some still shots from Steven Miller’s deep dive into Owl Cave. Notice the pre-staging of Phillip Jefferies’s scene in Season 3 Part 17: a ring of light, 8, owl symbol, and a “map” of Twin Peaks.

There are a lot of fictional and true horror stories about getting trapped in caves, and a whole genre called “subterranean fiction” that spans Dante’s Divine Comedy (where Hell is a system of caves) to The Three-Body Problem, Broken Earth Trilogy, LOTR, The Matrix, The 100, Kipo and the Age of Wonderbeasts, American Horror Story: Apocalypse, Lost, and so on. As we now move into homes designed with “Zoom Rooms,” we have to wonder if our technology is preparing us for this epochal transition underground already. The 10,000-year Clock of the Long Now is going to be kept in a cave. This collection of “underground wonders” are examples of possible locations.

What other movies or stories focus on caves? Frozen II for sure, with caves lifted from places in Iceland, maybe pointing to feminist themes in the movie? As they say, yonic is the new phallic!

Aronofsky’s film mother! features a secret cave and a classic “woman in trouble” scenario. At one point, the “mother” fingers a red stain on her floor that opens into a hidden cave where she finds her secret power: fire.

Caves also embody what feminist Elaine Showalter (1992) calls the “female wild zone.” It’s a place where women can harness and unleash their power. Considering the etymologies of “cunt”—a rabbit hole, a wedge, a Hindu goddess?—of course a “cave” protects a coded map to the mythical “Black Lodge.”

Perhaps all openings are caves are vaginas are sources of knowledge. Performance artist Carolee Schneeman famously explored these links in Interior Scroll (1975), versions of which took place inside actual caves. She speaks of a “translucent chamber of which the serpent was an outward model.” Bjork likes to sing in caves.

Caves within caves, openings within openings. Fire and oil are somehow involved. Micheal Garfield:

…my eyes the fire projecting shadows of imagination on the cave walls of my unborn and undying consciousness.

Grottoes

In any case, within art history, caves are where the strange is both hidden and spotlighted. There is a genre of oil painting, Grotto painting, that features chiaroscuro dramas in caves, where the mouth acts as a spotlight and the cave walls are curtains. What is staged often reflects a queerer or more alien—literally “grotesque” which derives from grotto and from Emperor Nero’s cavernous 16th-century palace, Domus Aurea, decorated with frescos representing bizarre motifs inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphoses—harpies, alien plants, women transforming into architecture, and more!

These decorative patterns—grotesques—are part of the history of surrealism, horror, fantasy, and are sacred vocabulary: wide-mouthed masks and puking gargoyles are used to decorate churches. Tangentially, Mikhail Bakhtin calls the mouth specifically a main feature of the grotesque (see The Monster in the Garden: the Grotesque and the Gigantic in Renaissance Landscape Design, 2016). Philip Thomson in The Grotesque: The Critical Idiom, points out aspects of “grotto-art” that we can spot in Twin Peaks: disharmony, abnormality, unresolved conflicts (“the payoff is that there is no payoff“), comedy, extremeness, the terrifying, the supernatural, and the disgusting. Like actual grottoes, grotesques and Twin Peaks are “unstable,” they could collapse at any second, and they are always reflecting something in the middle of a transformation. Susan Bowers, describing grotesques, sounds like she is describing Twin Peaks:

It is a flamboyant art form, brimming over with exaggeration, hyperbole, and excess, perhaps because exaggerated forms with exaggerated emotions are more symbolic and conducive to evoking the numinous, the uncanny, or the horrible.

The show isn’t just a “moving painting,” it’s a moving grotesque! Bowers: “The grotesque is a marvelous hybrid: it celebrates the body, but it also expresses psychic currents underneath the surface of the unconscious.” Twin Peaks and grotesques connect through another concept, the carnival. Nihat Can Kantarcit specifically compares HBO’s Carnivàle to Twin Peaks as they’re both about a settler town constructed as “a sacred site of the American repressed.” Quoting Bakhtin:

Filled with the spirit of carnival, the grotesque liberates the world from all that is dark and terrifying (…) All that was frightening in ordinary life is turned into amusing or ludicrous monstrosities.

Grottoes also refer to fake caves built for gardens and parks to evoke the spiritual. They are symbolic but also merely aesthetic: dark places contain deeper colors. Junichiro Tanizaki in his famous essay In Praise of Shadows even argues that shadows are the foundation of a human house: “In making for ourselves a place to live, we first spread a parasol to throw a shadow on the earth, and in the pale light of the shadow we put together a house.” Check out this kickass episode of Weird Studies Podcast about Tanizaki.

The Brain on Caves

A cave’s darkness, the “dark zone,” does things to us. Caves create conditions like sensory deprivation and Ganzfeld effects (akin to a James Turell light installation) that force the brain to deviate from its normal waking state. According to historian Yulia Ustinova, this is why, in ancient Greece, entering caves was a requirement for visionary or prophecy-giving experiences. I’m thinking of that part of Aronofsky’s film Noah, where Methuselah (Anthony Hopkins) lives in a cave, and Noah (Russel Crow) sees it in a dream and travels there to receive psychoactive tea that helps him envision the ark.

Apparently, after just a few days of total darkness, the human brain produces more DMT, the endogenous “spirit molecule” partially responsible for dreams and mystical experiences. More, studies using eye-tracking glasses indicate that eye-movement patterns during darkness resemble those during activities involving abstract and divergent thinking. Darkness seems to provoke creativity. Studies also suggest even just brief periods of darkness cause the brain to retrieve ambient magical consciousness. Professor Holley Moyes who studies the archaeology of religion thinks darkness not only makes us hallucinate, it promotes “magical thinking.” In her 2012 study, volunteers sitting in a dark room were more likely to answer questions in a “supernatural” way, while people sitting in a well-lit room answered the same questions more rationally—questions like: If you wake up and smell the pipe smoke of your dead grandfather, what is your first explanation? Check out Moyes’s TED talk.

It’s the darkness, but it could also be toxic fumes that alter our minds in caves. Some scholars think poisonous cave gasses were responsible for Greek histories and myths. It was probably ethylene, a gas that “produces feelings of aloof euphoria” (see For Delphic Oracle, Fumes and Visions). Ethylene plus a spike in DMT plus sensory deprivation effects? Given our four-dimensional selves, this all could have helped people foresee a future. Nevertheless, even when completely sober:

We do not behold a passive, inert scene but are immersed in a pulsing space, in the currents and energies of a world-in-formation, even in the darkness, and the light or lack of it is entwined with our sensing bodies, blurring distinctions between outside and inside. – Tim Edensor

Caves are important destinations for enlightened revelation, and if you don’t live near one, you can still “retreat” by closing yourself up in a dark room or closet, as we see in the Tibetan practice of a dark retreat. You can recreate some of the conditions of a cave, however, the dangers that heighten the body’s awareness cannot be replicated in a dark closet.

Leonardo’s Cave

As drug-laced sacred destinations, caves help information from the margins of consciousness get felt by the mind and transformed into art. Leonardo Di Vinci famously had a powerful experience with a cave as a young man. He stumbled upon one in the forest that caused him to feel two contrary emotions at once, fear and desire, “ — fear of the threatening dark cavern, desire to see whether there were any marvelous things in it.” He went in, and after that episode recorded in his diary, Leonardo started drawing helicopters, tanks, and advanced geometry. Ancient Aliens wonders if inside that cave Leonardo was beamed visions from elsewhere. Maybe he fell into a portal to the future, or to his own 4D “long self.” Around this time, he also went missing for two years! Alien abduction? Maybe, or maybe he was just laying low after being charged with sodomy—I think he was 24—a traumatic event he never got over. Leonardo remained celibate for the rest of his life.

What else do caves represent?

It’s not the world in which we live our daily lives, but the unseen, underground world where people live out their fantasies that has power. Forbidden desires and fantasies… ~ Virgil Ortiz

In Episode 25, the owl seen leaving the cave is different from the one who attacks Andy and the others. Did Andy release someone? I have a theory: maybe ancient people caught the owl/alien and walled it up in the cave with a map to the lodge so that, “In case owl is released, go here.” Or maybe whoever was trapped in there was good, which is why Andy was included as one of the chosen people.

I wonder if the large owl released from the cave is symbolic of another story. The nuclear radiation symbol found on Briggs’s neck that helps lead Cooper to the cave looks like a ceiling fan. Bluefrank over at the Twin Peaks Gazette thinks it’s the sigil for Chronozon, a “guardian” part of the Tree of Life (which is shaped like an 8). Intuition noticed that the entire symbol is a version of the Mystic Tetrad.

White Tail Falls

Eliade: “The discovery or projection of a fixed point—the center—is equivalent to the creation of the world.”

Twin Peaks is marked on the inside by Owl Cave and on the outside by the breathtaking White Tail Falls, which is a real place called Snoqualmie Falls, one of the tallest and most powerful waterfalls in the now-USA. Comparable to Niagara Falls (it’s actually taller than Niagara), some call it a Garden of Eden because it’s where, in the Snoqualmie myth-histories, the first humans emerged.

Can you imagine being able to visit the place where your people first emerged or landed? There is a pagan emergence place in Caesarea Philippi known as The Gates of the Netherworld, but Eden is lost to Christians. It’s “hidden,” but they couldn’t return there anyway because of the two angelic monsters guarding the entrance with their spinning swords of fire. Who are those guys? I like to think this image of a hidden garden and spinning gates of fire is a metaphor for the anaerobic bacterial now living in our guts—our cousins forced down into the muck by the fiery sword of the sun. Maybe, when oxygen began to fill the atmosphere, the ones who could “eat” and metabolize it were thrown out of “the garden,” destined to live above ground. Eden, our evolutionary birthplace, is now carried inside our bodies, as the ocean is carried inside of animal eggs.

Anyway, this Garden of Eden, Snoqualmie Falls, is now sacred for a second set of reasons. It’s one of the most popular pilgrimage sites for Peakers. Interestingly the falls are never really addressed in the show, which focuses instead on building a mythology around Owl Cave. I wonder if this was a way to respect the symbolic power of the actual site.

When you live next to your culture’s origin place, you get to visit there on class field trips and special occasions. Japanese people mark the top of Takachiho mountain on Kyushu their origin place, and the last time I was there I was surrounded by schoolchildren playing and taking pictures. Inversely, the Hopi and other Southwest tribes believe they emerged from the bottom of The Grand Canyon, specifically from a “sipapu” near the otherworldly blue waters of the Little Colorado. Rainbow Falls is the emergence place for the Zuni, Havasu Falls for the Havasupai. These sites are forbidden to outsiders, and backpackers who seek them out report strange accidents. Related, Sipapu is the name of the oldest Ski Resort in Northern New Mexico, opened by a white settler named Lloyd Bolander, “one of the last true pioneers.” Of course he named his hotel after a sacred Native American site.

Pits

Since pits are important landmarks in the show, let’s consider the concept of a sipapu. It’s a circular hole that marks “a portal between worlds.” What’s that? Frank Waters in The Book of the Hopi recalls stories about the first humans being led through a series of “Cave Worlds” before exiting into our world through the sipapu. Apparently, when we stepped outside of the pit, we morphed from lizard-like beings into human forms. Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny, and according to Larry Torres, the word sipapu in Uto-Aztecan refers to “the womb of the Earth.”

Clay also comes from pits by the river, and archaeologists like Ian Hodder talk about a near-universal “Age of Clay,” (aka the Neolithic) when humans lived in clay houses and through clay vessels. There are also a ton of humans-from-clay creation stories, like the Judeo-Christian one, where “Adam” is Hebrew for dirt.

Waterfalls and caves make pits, but pits are also dug. In northern New Mexico, there is a church, El Santuario de Chimayo, one of the most-visited holy sites in the US, which enshrines a circular pit famous for its “miracle dirt.” Like many religious art installations, the temple was built around the sacred place, which, of course, predates human settlement in that area. But in this case, it’s not the specific dirt so much as the spot that “charges” the dirt. According to Olsen Brad, the church replaces the dirt from the nearby hillsides every day, but as Belden Lane puts it, far from being a repudiation of the sacredness of the site, this transfer of dirt is proof of how the sacred extends itself into the profane (2001: 62).

Believers speak of a legendary light emanating from deep in the ground at Chemeyo, and how Bernardo Abeyta on Good Friday in 1810 dug into the light and miraculously found The Black Christ of Esquipulas. The site today, according to Lane, “is abuzz with the anguish of stored lament,” an atmosphere he can only compare to the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem.

The setup at El Santuario de Chimayo reminds me of art collective Postcommodity’s 2012 installation Do You Remember When, where they opened up a square pit of dirt in the middle of the gallery floor to create a sipapu.

The circular pit at Chimayo also resembles the pit enshrined in Bethlehem marking the exact site where Jesus was born.

A simulated sipapu is created in the bottom of a pueblo house or kiva directly across from the fire pit. There are also two pits in Twin Peaks, one surrounded by 12 sycamore trees, and the other marked by just one, perhaps the legendary 13th Sycamore that Cooper was, and was not, warned about by the Fireman. One pit is black and the other is gold.

Lastly, sacred pits famously configure the lives of the Bimin-Kuskusmin of Papua New Guinea. This tribe worships the oil that comes out of a pit in the forest. They believe the oil flows under the landscape itself in “the realm of the spirit world.” F.J.P. Poole (1986) quotes the tribe’s leader: “The oil is our blood, our semen, our bone, our heritage from our ancestors…our life.” This association makes the entire forest a realm of immense ritual and spiritual importance. A ten-year initiation is required before anyone can even set foot near the sacred pit.

Pits can be scary and are associated with quicksand, swamps, tar pits, and black goo. They can also refer to people and situations. In their episode on Part 14, Diane podcast remarks on how “Sarah feels like a pit,” and her face opens up like a dark pit or cave.

Back to the Falls

Slavoj Zizek famously marked Lynch’s universe the “ridiculous sublime,” and Allister MacTaggart, in Lynchian Landscapes and the Legacy of the American Sublime, points out that Lynch grew up in and around the landscapes of the Pacific Northwest, and this might explain the show’s “Emersonian transcendentalism.”

Waterfalls are classic symbols for the sublime, maybe also for America. Abraham Lincoln visited Niagara Falls in 1848 and brilliantly described it through geological, psychological, and philosophical perspectives. He said, for example, that “all the water constantly pouring down is supplied by an equal amount constantly lifted up by the sun.” Then Lincoln describes a kind of all-American myth-time that the waterfall opened up inside of him:

But still there is more. It calls up the indefinite past. When Columbus first sought this continent—when Christ suffered on the cross—when Moses led Israel through the Red-Sea—nay, even, when Adam first came from the hand of his Maker—then as now, Niagara was roaring here. The eyes of that species of extinct giants, whose bones fill the mounds of America, have gazed on Niagara, as ours do now… fresh today as ten thousand years ago.

“Giants.” In evolutionary anthropology, there is a theory that waterfalls (like boulders, caves, and pits) are a key to understanding the origin of religion. Jane Goodall recorded chimpanzees “dancing with excitement” around waterfalls, and she remarks how they will sit in the water at the base and stare up at them as if in a state of aesthetic appreciation. This could be due to the water’s sublime and symbolic power (water is life), but it could also be due to the trippy aftereffects that staring at the constantly moving water has on the brain. The “waterfall illusion” is when we hallucinate movement when we look at something stationary after staring at something moving in one direction for some time. This can also mess with our sense of time.

Waterfalls also symbolize orgasms, and according to philosopher Sara Heinamaa, they “frame crucial romantic encounters in several popular movies,” like The Lion King and Avatar. “They allude to sexual climax, which thus appears as an explosive or overflowing event.” Maybe on some level, the opening credits of Twin Peaks: The Return give us subliminal orgasms: music swells, water gushes, curtains billow, world spins. Similarly, waterfalls may represent vomiting and other cathartic expulsions.

Waterfalls have been used to explain a property of black holes. Bill Unruh theorizes that light crossing the horizon of a black hole is like sound passing over the edge of a supersonic waterfall. It cannot escape. “The analogy turned out to be more accurate than Unruh initially thought. Eight years later, in 1980, he realized that the equations of motion for sound in the waterfall analogy were identical to those describing light at the horizon of a black hole.”

Lastly, we should note that New Zealand just recently granted The Whanganui River the status of a legal person with rights and responsibilities. Alas, waterfalls and other rivers are people, too. In Getting Dirty, Anishinaabe scholar Melissa Nelson points out that there is an entire genre of Indigenous oral stories from the Pacific Northwest and elsewhere about intimate relationships between humans and other-than-human entities like logs, rivers, stars, even winds. People form relationships with geological formations as well, especially irregular stone outcroppings in the landscape.

The Boulder

Standing on this rock, therefore, we may fancy a magic power ushering us into the presence of our fathers. – James Thacher, History of the Town of Plymouth, 1835

Like waterfalls, caves, and pits, boulders are a big deal in our collective unconscious. Archaeologist Christopher Tilley (2004) argues that our prehistoric identities were created predominantly near and by boulders in the landscape. Irregular stone outcroppings were landmarks and social sites — pegs and attractors within our cognitive maps of the world. Viewing boulders was an important process by which we could tap into ancestral powers at specific locations, and it helped us anchor identity in those powers and locations (see Keith Basso’s Wisdom Sits in Places about Apache boulders that tell stories and keep people connected to their ancestral languages and morality). More, researchers in the field of spatial psychology propose Prospect-Refuge theory (Appleton, 1975; Dosen and Ostwald, 2016) suggesting humans evolved to seek out higher and safer vantage points. Alas, Richard’s path up to that boulder was laid down by millions of years of hunter-gatherer instinct.

Humans also, in theory, seek out landscapes with physical characteristics that support certain psychological dimensions.

Erratics

Boulders become vantage points, landmarks, sites for cultural transmission, art, and, in Twin Peaks, they become a site for killing doppelgangers and murdering sons. This resonates with the Biblical “Binding of Isaac,” where Abraham takes his son to die atop a large stone on Mount Moriah.

This boulder looks out of place, an erratic, glacially transported here and thus probably the center of a local legend. Indigenous stories abound of boulders that were once giants, monsters, gods, even human people that turned into stone and may one day turn back, such as the Lakota Standing Rock, the Paiute Stone Mother, and the Navajo Shiprock. Celtic landscapes are likewise filled with magical boulders, like Lia Fáil, a coronation stone that was said to roar or shriek when a true king sits upon it. Another legend says it roars only when a false king sits on it. Is this what happened to Richard? There is also the great Cat Stone aka Stone of Divisions near Ireland’s geological center, on the Hill of Uisneach, that marks where the goddess Éire (Ireland’s namesake) is said to be buried.

Large stones are found in the center of all major religions. Interestingly, the Abrahamic God is called a “rock” many times in the Bible. The Black Stone, Hajal al Aswad, is enshrined at the Cube or Kaaba in Mecca. In the myth, this meteorite was dropped into Eden as the first altar. There is also the Christian “Stone of Anointing,” Japanese Iwakura or Ishigami stone gods—the Sessho-seki, a stone said to kill anyone who comes into contact with it, recently made news by cracking open on March 5th, 2022; the Stone of Scone, The Blarney Stone, Excalibur’s stone, and more. No doubt a stone’s silence, indifference, and durability make it a perfect receptacle for our dreams of transcendence.

Boulders are mini-mountains, and in settler histories of what we now call the US, the most famous one is Plymouth Rock, where the original Pilgrims first landed. Originally, this boulder was the same size as the one we see in Twin Peaks, but like the body of a saint, fragments were carved off, venerated and distributed far and wide. “Its very dust is shared as a relic,” says Alexis de Tocqueville in 1835. Over the course of 400 years, it went from a 200-ton boulder to a five-by-six-foot rounded fragment which is now enshrined in what looks like a Roman temple in Massachusetts. Indigenous American activists sometimes bury Plymouth Rock, as it is also “a monument to murder, slavery, theft, racism and oppression.”

Steven Miller found the location of the boulder from Part 16, what he calls “False Coordinates Rock”—it’s in Big Sky Movie Ranch in Simi Valley, California, “the largest ranch inside the Los Angeles Studio Zone.” It turns out the boulder, like the cave, is a movie star!

Conclusion

There is an unaccountable solace that fierce landscapes offer to the soul. They heal, as well as mirror, the brokenness we find within. – Beldan Lane

The interior landscape is influenced by the exterior. Twin Peaks encourages us to overflow like a waterfall, go spelunking in our souls, feel like a pit, and disintegrate atop an ancient boulder. It employs familiar landscapes that resonate deeply with our bodies and minds.

Like many of us, I want to know to what extent Twin Peaks is linked to our religious ideas and narratives of place in the “real” world. How does Twin Peaks shape our lived and imagined landscapes? “The eyes see only what the mind is prepared to see.” Conversely, how do our lived landscapes shape our experience of Twin Peaks? We can glean insights from Landscape Studies.

The history of the concept of landscape is tied to painting, photography, phenomenology, the study of visual perception, geography, and religion. When approaching landscapes of the sacred, theologian Beldan Lane thinks we should move away from the comfortable “cognitivism” of people “in” space, and towards a “non-dualistic phenomenology that recovers the wholeness and nonduality of place.” He says,

A sacred place is not simply a unique site magically “possessed” by chthonic forces. Nor is it a topographical wax nose that can be culturally twisted into anything one makes of it. A difficulty with both approaches is that the perceiver largely ignores the actual particularities of the place itself. It becomes a blank slate on which divine or human meanings are arbitrarily inscribed — by means of luminous revelation on the one hand or cultural construction on the other.

I believe Twin Peaks encourages us to consider a more non-dual “enactive approach to cognition,” where we can transcend the inside-outside, subject-object split. We can see through the dream of an autonomous, disembodied soul or witnessing consciousness “just aware” of everything, and feel how perception is really a cooperative, interactive process—a handshake between the organism and its environment.

Subject and site inter-act, so much so that different characters construct different worlds through their embodied interactions with it. Likewise, living lodge spaces and the actual physical locations engage with each other, “not as independent entities per se by as agents within a material matrix of becoming” (Vasquez 315). As Tim Ingold puts it, “Organism plus environment should denote not a compound of two things, but one indivisible totality.”

A human’s experience and an owl’s experience of the same cave will be very different. Nicole Boivin talks about a water bug “enacting” the water not as a place to swim, but as a place to walk, thus pointing out how engagement with the environment even constructs its material properties to a degree. For those of us who spend a lot of time “in” Twin Peaks, we may want to pay attention to this intimate reciprocity.

We live in the storied place as it lives inside us. Religions like Twin Peaks are external and internal landscapes, processess, or what Thomas Tweed calls sacrospaces: they move and impel us to move. Maybe we should approach Twin Peaks not as a story but as an ecological, corporeal, and semiotic-cognitive-numinous process—aka a sacred landscape, a religion. Tweed (2006: 79): “As spatial practices, religions are active verbs linked with unsubstantial nouns by bridging prepositions: from, with, in between, through, and most important, across. Religions designate where we are from, whom we are with, and prescribe how we move across.”