Let’s liberate the Canadian landscape from the Group of Seven and their nationalist mythmaking

Material warning for Indigenous visitors: colonial violence is reviewed in this essay.

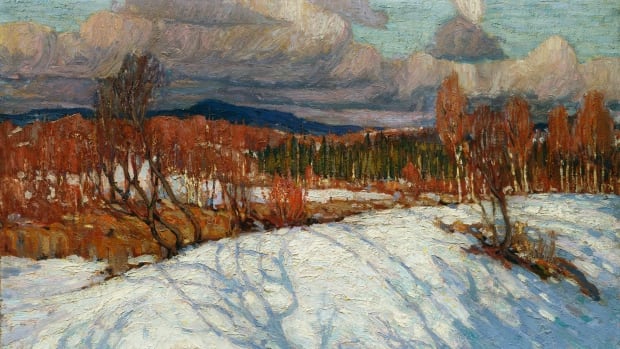

It has taken me a extended time to reconcile the Group of 7 and their location in Canada’s mythology. On one particular hand, I like their paintings: they are gorgeous and assorted in their landscapes, a illustration of these lands in all their sacredness and lifestyle. On the other hand, they suffocate. The Team of Seven’s nationalist tale surrounds us like the prints of their get the job done that hold in Canada’s households, educational institutions, and galleries.

We are explained to to see their paintings — an necessary chapter in our nationwide story — as essentially Canadian. But the histories of Indigenous men and women on these lands, and the sacred and sovereign connection we have with this land, are not mirrored in the is effective of the Group or their peer and impact Tom Thomson.

Irrespective of how we are intended to see them, the Group’s paintings do not symbolize localized landscapes infused with history from pre-speak to to the colonial present. Instead, they are a reproducible graphic of a standardized Canada, exactly where a jack pine is a stand-in for a purple leaf on a flag. This way of viewing is countrywide in perfect and colonial in gaze.

If the Group of Seven’s paintings are meant to determine Canada, what does it necessarily mean that so numerous tales of the lands’ background are deliberately lacking? And what is dropped by this colonial gaze of the Group and the land?

The Team of Seven mostly painted in the Canadian wilderness. They have been particularly influenced by the sketching trips they went on in Algonquin Park, led by Thomson, who resided there for a lot of the year toward the stop of his life. It was the location exactly where he labored, sketched, and died. The Canadian pure landscape, in all its natural beauty and risk, was an affect that mythologized these painters as artist-bushmen, a new breed of artist born from the rugged wilderness of Canada.

When I 1st began going for walks through the National Gallery of Canada, pausing in entrance of paintings, I wondered why the Team seldom painted First Nations. I go through later on that Canada’s authorities officers compelled out the Îyârhe Nakoda in Banff, then the Coast Salish in Stanley Park, and afterwards the Algonquin in Algonquin Park. Initially Nations ended up forbidden from searching, gathering or travelling via their territories. The land was now a government-founded park, a Canadian park, an exclusionary park.

Continuing the operate of the bureaucrats who designed Canada’s community park technique, the Team of Seven painted the landscape as a terra nullius — “uninhabited land” in Latin. If Indigenous peoples or structures did show up, they ended up often faceless, a natural phenomenon to be witnessed by the colonial gaze.

When anything is erased, a blank sketchbook is all set for its artist. Nationalism desired the artist-bushman to conquer the imaginary landscape as it needed the pioneer to do so with the authentic landscape.– Matteo Cimellaro

I can only hope that it really is not still provocative to say, historically, Indigenous erasure and settler nationalism have been synonymous. Two sides of the coin. The Queen stamped opposite the caribou, the beaver, the bear, and so on. A philosophical basis for this development starts in England in the 17th century. In his “2nd Treatise of Government,” John Locke suggests that when you combine your labour with nature, you develop private house that is owned by you and excludes other people. But what of a nationalizing labour — a cultural labour that creates a country’s mythology?

This nationalizing labour excludes all that is unseen and unspoken. In the Team of Seven’s depiction of the Canadian wilderness, 1st Nations were largely out of sight and silenced. Immediately after governing administration policy designed this deliberate emptiness, the Group’s paintings colonized landscapes within what Northrop Frye referred to as the Canadian creativeness. Via this painting and viewing, a property was sanctioned — a property we call Crown land.

The struggle in opposition to Crown land continues these days. It is a battle to reclaim sovereignty — a preeminent want for 1st Nations to have relations with their lands back, soaring from the accountability to steward Mom Earth for potential generations. Nonetheless, this is Canada, and like the Group’s artworks, Crown land continues to be for private fascination and at any time-increasing gain. (A painting by Lawren Harris that marketed for $11.2 million in 2016 is the most expensive Canadian artwork ever bought at auction.)

In her essay “Land as pedagogy: Nishnaabeg intelligence and rebellious transformation,” Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg writer Leanne Betasamosake Simpson equates aki, Anishinaabemowin for land, with liberation. She writes: “Aki is also liberation and freedom — my flexibility to build and keep interactions of deep reciprocity inside a pristine homeland that my Ancestors handed down to me. Aki is encompassed by freedom, a flexibility that is guarded by sovereignty and actualized by self-determination.”

Simpson is pointing to a independence that is about human dignity taken by settler nationalism. By way of a nationalist violence, Canada endeavoured to depart Indigeneity in the earlier tense by way of residential colleges, Indian agents, and bans on cultural and religious techniques.

When a little something is erased, a blank sketchbook is completely ready for its artist. Nationalism wanted the artist-bushman to conquer the imaginary landscape as it needed the pioneer to do so with the true landscape. The Team of Seven, hoping to distinguish by themselves from a European tradition, were happy to deliver these nationalized paintings.

Now it is time to issue no matter whether we, as seers of paintings and landscapes, want to continue on an exclusionary myth of Canada marked by its rugged landscape and rugged painters. The recourse is to reject the colonial gaze: to see things as they are, blemished by the cruelty of background.

I am asking you to meticulously look at the historic truths when you see the paintings of the Team of 7. What do you see — Canada? What does that suggest? It is a landscape, but who is the proprietor? What does that ownership suppose? Is there an owner?

The artwork allows us have an understanding of historical past by way of what it represents and how and why it can be reproduced. The Group’s paintings and their reproductions played a vital role in forming Canada’s nationwide mythology. Now, the Team of Seven should be liberated from the prison of Canadian nationalism. Legitimate flexibility and sovereignty of the land may well rely on it.