The art exploring the truth about how climate change began

The art exploring the truth about how climate change began

(Image credit: Louis Henderson/ Courtesy of the artist)

A new art exhibition offers a fuller, more rounded view of humanity’s impact on the Earth – by tracing its link with colonialism. Precious Adesina talks to the artists.

I

It has been more than three decades since climate change became front-page news. In 1988, The New York Times ran an article titled “Global Warming Has Begun, Expert Tells Senate”. Ever since, discussions on the crisis have predominantly focused on how the state of the world has been affected by humans since the Industrial Revolution in the West – and with good reason. The Earth’s temperature has increased by 0.07C every decade since the late 19th Century, a rise that has been linked to the mass burning of fossil fuels. Yet a new exhibition of work by various artists suggests that we must look further back in time and analyse the issue from a non-Western perspective in order to get a fuller picture of the current emergency.

More like this:

– Why we need powerful symbols

– Climate change clues hidden in art

– Facing up to a horrifying history

The group show We Are History: Race, Colonialism and Climate Change opened to coincide with 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair at London’s Somerset House. Through the lens of 11 artists who have a personal relationship with the Caribbean, South America and Africa, the exhibition looks not only at the roots of global warming, but also at how it impacts the developing world. By looking back, the link between the world’s environmental issues, colonialism and slavery is highlighted. Also explored is how these problems still have a disproportionately negative impact on certain countries. A study released in 2020, published by two archaeologists, revealed how colonisation forced residents in Caribbean communities to move away from traditional and resilient ways of building homes to more modern but less suitable ways. These habitats have proved to be more difficult to maintain, with the materials needed for upkeep not locally available, and the buildings easily overwhelmed by hurricanes, putting people at greater risk during natural disasters.

From the forest to the concrete (to the forest) by Alberta Whittle explores the legacy of colonialism (Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Copperfield, London)

Among the exhibits is Barbadian-Scottish artist Alberta Whittle’s film from the forest to the concrete (to the forest), 2019, which directly explores this topic, documenting the effects of Hurricane Dorian in the Bahamas. The 10-minute-long film is stamped with the date 09.09.19, nine days after the disaster. “Africa produces 4{6d6906d986cb38e604952ede6d65f3d49470e23f1a526661621333fa74363c48} of the world’s greenhouse gases, the whole continent, but yet it is so at the front line,” Whittle told culture magazine The Skinny. The artist wants people in the UK to see the disparity between their own comfort and the relative lack of comfort of their non-Western counterparts. She intertwines a number of performances with footage of destruction. “[There was] a terrible hurricane that moved through the Bahamas last week,” she said at the time of its premiere. “But what I see in the weather in the news in the UK, is ‘Oh isn’t this wonderful, we are about to go through a period of sunshine’.”

What this exhibition asks is: who we are really talking about when we question how our collective actions are having an effect on the environment? According to the curator of the exhibition, Ekow Eshun, if we don’t allow the people in emerging countries to speak for themselves, we force them out of the conversation and into one that isn’t consistent with the facts. “Otherwise we end up repeating the same narrative that we’ve repeated for a long time that somehow people in the developing world are supporting characters in the drama, rather than communities that are directly affected [by climate change],” Eshun tells BBC Culture.

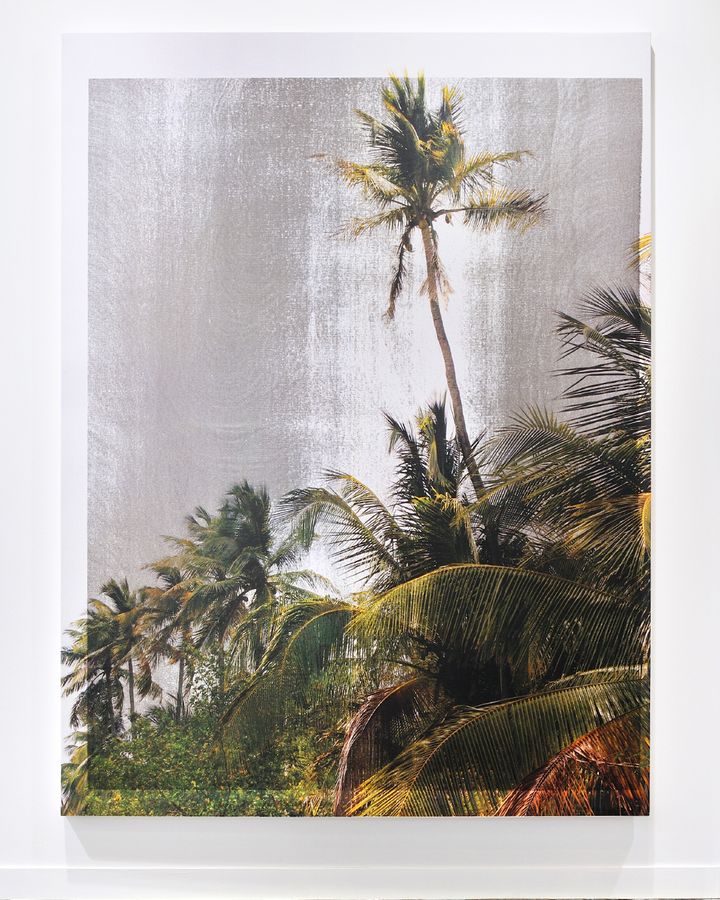

Louis Henderson’s video installation is an adaptation of the poem The Sea is History by Derek Walcott (Credit: Courtesy of the artist)

Similarly, British filmmaker Louis Henderson focuses on how the West is primarily responsible for the disruptions to the natural world that humans have caused in his almost 30-minute long video The Sea is History, 2016. Henderson adapts the poem of the same name by Caribbean poet Derek Walcott. In his poem, Walcott discusses the effects of colonisation on a community’s culture, and claims that the history of these places is hidden in the sea. The footage in Henderson’s piece features mesmerising shots of Lake Enriquillo, a lake in the Dominican Republic that often floods due to rises in sea temperature.

Through this, the artist explores how the exploitation of the island for its natural resources, the genocide of the indigenous population and the importation of enslaved people have contributed to the global emergency. “I am interested in identifying Columbus’s 1492 arrival on the island of Ayiti/Kiskeya (nowadays known as Haiti and the Dominican Republic) as a potential starting point for the climate crisis the world is facing today,” Henderson tells BBC Culture. “I believe it’s important to continually analyse and attempt to understand the effects of the afterlife of transatlantic slavery, both on a local and a global scale, and how it impacted the Earth’s geology and its ecosystems.”

Hidden history

Much like Whittle and Henderson, the collaborative duo Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla explore how outsiders have impacted the Caribbean, but they take a different approach. Their screen-printing method for the series Contracts uses layers of black ink to taint the beautiful scenery they depict. “What seem to be conventional pictures of a beautiful destination are disrupted by a layer of a single colour ink, shrouding the idyll partly or completely,” say the duo. “We live and work in Puerto Rico, a Caribbean island that, since the colonial period, has been systematically exploited for its natural resources… As climate change makes weather events more severe, from droughts to hurricanes, the already vulnerable island is put in an even more heightened state of precariousness.”

Artists Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla explore climate impact (Credit: Courtesy of the artist/ Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris/ Sebastiano Pellion di Persano)

Contract (AOC L), 2014, shown at the exhibition, is a piece that is part of the larger series. In it, the pair catalogue sites in Vieques, Puerto Rico, where palm trees were used as markers by the US military to highlight where hazard waste was disposed. The areas are now managed by the US Department of Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service as conservation zones, according to the artists. “This paradoxical designation denies the underlying environmental and health risks of the dumps – so toxic that in 2005 they were placed on the US Environmental Protection Agency’s Superfund National Priorities List,” they say.

Colombian artist Carolina Caycedo says that the only way to truly move forward is to listen to the people who are explicitly affected by these changes to the ecosystem. “We urgently need to look at what communities that are actually on the frontlines are proposing on a grassroot level, since they are the people who are directly impacted by the climate crisis,” she tells BBC Culture. Her research-based art project, Be Dammed, investigates the environmental and social consequences of dams throughout Latin America. “By [looking at] different case studies in the Americas, I’ve had a chance to collaborate with some of these communities to highlight alternatives to these large infrastructures,” she says.

A Universal History of Infamy by Carolina Caycedo is among the exhibits at the new show We Are History (Credit: David de Rozas/ Museum Associates, LACMA)

While none of these artists offer a hyper-specific call to action, collectively they show how climate change has affected the countries they belong to, or associate themselves with, and the importance of putting global issues into perspective. As Eshun puts it: “I think it’s important that those voices and those perspectives are heard and not simply as victims but heard as people who have agency and autonomy, and in this respect they’re heard through the voice of artists.”

We Are History: Race, Colonialism and Climate Change is at Somerset House, London, until 6 February 2022.

Black History Month takes place throughout October in the UK.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.