A road runs through it: Looking for solutions for wildlife along Highway 191 between Bozeman, Big Sky | Environment

When wildlife researcher Patricia Cramer takes a bird’s-eye view of a landscape, she likes to imagine a black bear moving across it, navigating both natural and man-made features. Where might that bear find food and water? What paths might it follow to meet potential mates? Where would it tuck in for a nap, or den for the winter?

The thought that follows is grimmer: “How in the world is that animal going to be able to do that tonight — or any night — and not get killed on the road?”

Cramer, a self-described “queen of wildlife crossings,” has been studying the intersection of transportation and ecology for the better part of two decades. During that time she’s come to think of roads as representative of the ways in which humans have dominated and fragmented the natural world.

A former professor of wildlife ecology at Montana State University and part-time resident of Gallatin Gateway, Cramer takes particular interest in U.S. 191, a serpentine two-lane highway that parallels the Gallatin River and bisects tens of thousands of acres of national forest that provide habitat for grizzly bears, black bears, elk, moose, deer, bighorn sheep, red foxes, wolverines and cutthroat trout. Set in a river corridor of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem thick with both humans and wildlife, Highway 191 hosts a steady stream of motorists traveling between Bozeman, one of the fastest-growing communities of its size in the country, and Big Sky, a resort town in the midst of a construction and tourism boom.

Between residents of Bozeman and Belgrade commuting south for work and vacationers bound for Big Sky or West Yellowstone, Highway 191 accommodates as many as 13,500 vehicles per day on a stretch of asphalt that in many places doesn’t meet federal and state highway standards for width, turn-outs, passing lanes and roadway curvature, according to a 2020 report on the 191 corridor between Four Corners and Beaver Creek (just south of the turnoff to Big Sky).

The report also reveals an increase of more than 130{6d6906d986cb38e604952ede6d65f3d49470e23f1a526661621333fa74363c48} in the number of vehicle crashes, from 64 in 2009 to 157 in 2018. One of the more dangerous stretches of 191 inside Gallatin Canyon saw as many as 39 crashes per mile during that same span, including seven fatal crashes and 27 that are suspected to have resulted in serious injuries.

The pressure on wildlife — particularly deer, elk, bighorn sheep and moose — is immense. Twenty-four percent of all crashes tallied in the report involved wildlife — more than any other type of accident studied. That’s more than twice the statewide rate of accidents involving wild and domestic animals, according to Montana Highway Patrol data from 2015.

Elk cross the road in the early morning south of Bozeman.

A 2016 report based on animal carcass data found that a 10-mile stretch of U.S. 191 between Four Corners and the mouth of Gallatin Canyon is No. 2 in the state for wildlife carcasses reported per mile: 4.03 during the fall, when migration and breeding patterns spur ungulates to movement. The report, which was prepared by Bozeman-based nonprofit Center for Large Landscape Conservation, also included a tally of the total number of wildlife carcasses reported on Montana’s roadways between 2010 and 2015: 36,940, an average of 6,156 per year.

To help bring those numbers down, the report’s authors advise motorists to scan the roadside for wildlife, take special care in the dawn and dusk hours when animals are most active, slow down around blind corners, and use high-beam headlights in the absence of oncoming traffic.

But the most effective measures to reduce wildlife-vehicle crashes will require buy-in from transportation planners that oversee highway improvement projects. Cramer said wildlife crossings, which physically separate animals and motorists, are one of the best tools to reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions and support habitat connectivity, particularly at traffic volumes like those common on Highway 191. But Montana’s appetite for such measures appears to have waned in the past decade.

Cramer said there’s been a “precipitous drop-off” in the number of crossings MDT has installed in the past 15 years, which is consistent with the observation of Western Transportation Institute road ecologist Marcel Huijser, who recently told Montana Free Press that Montana has become “stagnant” developing crossings in the past decade. Rob Ament, Huijser’s colleague at WTI, notes that Highway 191’s route through Montana is one of the only highway segments in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem lacking a wildlife crossing or a completed study that could inform future crossings.

“Although mitigation measures may require large initial investment and maintenance expenses, the threshold collision rate at which these measures become cost effective is surprisingly low in some cases,” the CLLC report notes. “For example, the benefits of installing fencing with the underpasses and jump-outs outweigh the costs over a 75-year period [the approximate lifetime of a wildlife overpass] for sections of highway with at least 3.2 deer-vehicle collisions per kilometer per year.” For comparison, the carcass-per-kilometer rate in the section of 191 referenced in the report is nearly twice that: 6.7. And that includes only fatally injured animals — it doesn’t take into account those that were struck by vehicles but made their way off the roadway.

DEVELOPMENT, ZONING, AND THE “BARRIER EFFECT”

The fix isn’t as straightforward as securing funding and installing the infrastructure — itself a considerable ask, given that overpasses cost between $1 and $7 million, and the price tag for underpasses ranges from $250,000 to $600,000. Rob Sisson, a conservationist with decades of experience as an elected officeholder in southern Michigan, knows this well.

Sisson is a resident of Gallatin Gateway, a rural community of 884 people about halfway between Four Corners’ commercial sprawl and the mouth of Gallatin Canyon. He has a front-row seat to the carnage on Highway 191. The highway itself is just part of the picture, he said.

Sisson said he’s become increasingly frustrated watching some of the best agricultural land and wildlife forage in the valley transformed, parcel by parcel, into a commercial strip. He said development and traffic are cutting off one of the last viable highway crossings for elk traveling between the Spanish Peaks and the foothills of the Gallatin Range. To the south, the canyon pinches in — its tall granite walls are popular with rock climbers — and there’s scant open space on either side of the highway. Commercial development to the north hampers wildlife movement, he said.

A small herd of elk get up after bedding down in a field near Gallatin Gateway on Thursday, Jan. 6, 2021.

“There’s just no place for the elk to go,” Sisson said. He tends to center the blame on Gallatin County government. “The county’s allowing it to be developed with no care for wildlife,” he said. He acknowledged that Gallatin County recently adopted a new growth plan directing commissioners and county staffers to take wildlife impacts into account, but said he’s underwhelmed by the document.

“Great — you’re too late,” he told MTFP in early November. “It has no teeth in it. It’s a suggestion.”

He said he’s looking for something stronger: zoning regulations to “put the horse in front of the cart” and prevent the Gallatin valley from succumbing to “runaway, out-of-control, unplanned, destructive development.”

Huijser echoes Sisson’s concern, saying that for a crossing to work well, transportation planners need assurance that the area surrounding it isn’t destined to be transformed from good wildlife habitat to poor habitat by virtue of development or changes in land use. Both Sisson and Huijser also acknowledge that zoning can be a tough sell in much of Montana, and in the American West more broadly.

“We have a lot of habitat loss [and] species loss over time. Natural resources, including space, are not endless,” Huijser said. “Once we acknowledge [they] are finite, then the logical step is to do landscape planning, spatial planning.” Huijser said he finds such efforts to be an important exercise for communities to prioritize what they value. Acting as if natural resources are infinite won’t end well, he said. “Our natural ecosystems [and] the species living in them will unravel.”

Last year, Sisson hit a roadblock in his attempt to launch a Gallatin Gateway zoning effort. He and his neighbors gathered signatures for a citizen zoning initiative but were deterred by the cost to hire a lawyer to prepare draft regulations, a new requirement implemented by the state Legislature last spring.

With his concerns escalating, Sisson went so far as to find $1 million of tentative funding for a wildlife overpass himself. But he hasn’t secured undeveloped land to build it on, and he worries that his window for finding such property is closing.

In the past couple of months, heavy machinery has been preparing what appears to be new commercial development in the immediate vicinity of his property. He wonders what will happen to the elk herd he’s enjoyed watching on a near-daily basis in an area he’s dubbed “the last 100 acres.”

Sisson’s urgency and frustration with the Gallatin County Commission is palpable in his writing about the issue, but commissioner Zach Brown said the commission is constrained in what it can legally do. “State law is very pro-development,” Brown said. “[It] really defines what we can and can’t do in terms of development review.”

Julie Cunningham, a biologist who does aerial ungulate counts for Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks, said building a wildlife overpass isn’t a decision to take lightly. She said it doesn’t make sense to build a crossing that animals won’t use, whether because it’s poorly aligned with wildlife movements or because land use in the area is still in flux. A multimillion-dollar overpass adjacent to a parcel destined to become a brightly lit strip mall or densely populated subdivision won’t work well. Road ecologists call such structures “bridges to nowhere.”

Rapid growth throughout Gallatin County, which grew by 33{6d6906d986cb38e604952ede6d65f3d49470e23f1a526661621333fa74363c48} between 2010 and 2020, presents real concerns about finding durable solutions to habitat loss and traffic impacts, Cunningham said. She thinks it makes more sense to focus on conservation efforts to protect wildlife habitat in perpetuity.

Elk cross the road in the early morning in Gallatin Gateway.

She also said that the ways animals use a landscape and interact with human presence are complex. When she looks at the movements of Gallatin Valley’s elk herds, she sees something different from Sisson. Whereas Sisson describes an “elk highway” — a highly trafficked game trail cleaved by US 191 — Cunningham said her data shows something different.

She put radio collars on elk on the west side of the highway to get a better sense for their movements and found that they “did not routinely cross 191.” She said Sisson might see lots of elk near the highway, and he may even see elk occasionally cross it, but the highway doesn’t appear to be inhibiting a migration corridor. What she sees is two distinct herds, one to the west of 191 that she calls the Spanish Peaks herd and another to the east she calls the South Bozeman herd. She said the two herds tend not to spend much time on each other’s turf.

But wildlife advocates say the existence of a migration corridor is not the only consideration that should come into play. First, crash and carcass data indicate that a significant number of animals are getting hit by cars on 191 south of Gallatin Gateway. It’s mostly deer — as many as 66 per half-mile during the 10-year study period — but also elk.

Second, after a certain threshold wildlife strikes tend to go down as traffic increases. As traffic on a route intensifies, animals start avoiding it altogether, Cunningham said, contributing to what road ecologists call the “barrier effect” of highways.

While that might be good for motorists spared dangerous and expensive collisions, the picture is more complicated for wildlife. Animals might be less likely to die on the highway, but their movements to find food, mates and refuge from wildfire or drought are more restricted.

One study examining elk movement in Arizona found that when traffic volumes exceed 100 vehicles per hour, elk are rarely found within 100 meters of the road. By the time traffic volume reaches 500 to 600 vehicles per hour, elk routinely stay more than 100 meters away. Rush-hour traffic south of Gallatin Gateway commonly exceeds 1,000 vehicles per hour during summer weekday evenings, and shoulder season weekend traffic peaks still top 600 vehicles per hour.

A similar effect is at work with grizzly bears, which are even more road-shy than elk. A 2015 study examining the movement of northwestern Montana grizzlies fitted with GPS collars found that “crossing frequency was strongly and negatively correlated with traffic volume, reaching zero when traffic volume exceeded 100 vehicles per hour.” More recent radio collar data analyzed by FWP research biologist Cecily Costello supports the conclusion.

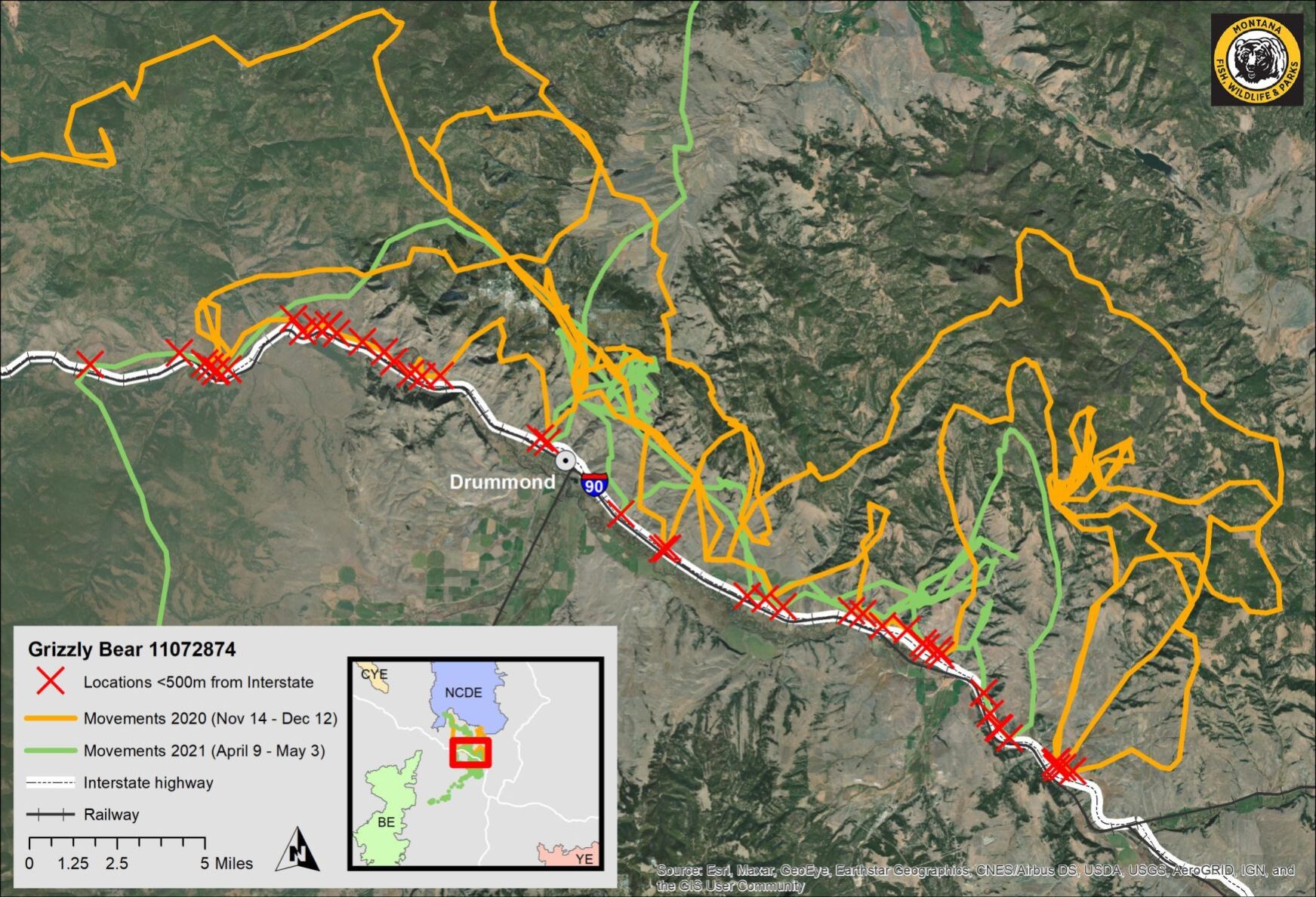

FWP biologist Cecily Costello used GPS data from a collared grizzly bear to better understand how Interstate 90 influenced the bear’s movements. Costello estimates the subadult grizzly dubbed “Lingenpolter” tried to cross the interstate 46 times between the fall of 2020 and the spring of 2021.

Costello used data from a collared subadult grizzly dubbed “Lingenpolter” to understand how Interstate 90 near Drummond impacted his movements. On the map above, Costello used red Xs to mark when Lingenpolter’s GPS collar indicated he was within 500 meters of the interstate. She estimates the bear made at least 46 attempts to get to the south side of the interstate between fall 2020 and spring 2021. He finally crossed successfully last May, apparently by walking beneath interstate and railroad bridges that span the Clark Fork river.

A PATH FORWARD

Supporting wildlife movements is the north star of the Center for Large Landscape Conservation, the nonprofit that prepared the report analyzing carcass hot spots on Montana highways. CLLC’s office also happens to be located just 7 miles east of the section of highway referenced in its carcass report.

After trying to fund projects that support wildlife movements across U.S. 191 for several years, CLLC is positioned to give the highway with the state’s second-highest wildlife carcass rate — and one of the only highways in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem without a wildlife ecology treatment — a closer look. The organization received a $50,000 allocation from the Big Sky Resort Tax Board last year and has teamed up with Western Transportation Institute to tailor a smartphone app called Roadkill Observation and Data System, or ROaDs, to gather information about conflict zones and wildlife movements on Highway 191 using citizen scientists, i.e., everyday motorists traveling the highway.

The project launched late last summer. Its goal is to bring more detail to the conversation about where animals are hit and where they’re spotted while increasing motorist awareness of wildlife along the highway.

CLLC hopes to pair agency data like aerial wildlife counts and GPS collar data with live and dead animal sightings provided by app users. Later project goals include prioritizing sites for wildlife accommodations by evaluating their crash frequency and value for habitat connectivity as well as land-use considerations and engineering feasibility. Other objectives include providing more detail about smaller-bodied and rare species not considered in other data sets (there’s not much carcass data for, say, racoons or foxes in MDT’s counts since they’re less likely to obstruct the roadway).

At the state government level, Montana is starting to get more creative with funding sources, which could help biologically centered wildlife accommodation projects get off the ground. In 2018, MDT, FWP and Montanans for Safe Wildlife Passage formed the Wildlife and Transportation Steering Committee. Part of its goal is to identify opportunities to bring private funding for crossing structures to the table. The committee initially met quarterly, but has recently started meeting monthly, according to MDT Environmental Services Bureau Chief Tom Martin.

Martin added that the group has identified two candidate areas for crossing structures: one on Interstate 90 in the Nine Mile area west of Missoula, and another on Highway 89 north of the Gardiner entrance to Yellowstone National Park.

The conversation about one of the busiest highways cutting through the GYE is happening against a national backdrop of historic new funding for wildlife crossing initiatives. The $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill passed by Congress in November includes $350 million for such projects.

CLLC road ecologist Elizabeth Fairbank said she hopes the national momentum for crossing initiatives will be thoughtfully directed, and that Montana’s approach to crossings will be systematic, data-informed and carefully prioritized.

Ben Goldfarb, a Spokane, Washington-based environmental journalist who’s writing a book about road ecology, said the new federal pilot program has been years in the making.

“This was definitely a long-standing dream of environmental advocates and road ecologists,” he said. “There’s [now] a dedicated pot of money to move the field forward in interesting and progressive [ways].”