‘Everyone is an artist. We just need to learn how to see’: Zimbabwe’s My Beautiful Home contest | Global development

A crescent moon hung high in the starry sky above Matopos village in Zimbabwe, while an eagle owl was hooting on the thatch roof as Peggy Masuku crept out of her clay-brick home.

It was 4am, the hour before daybreak, and two weeks before the competition she had put every fibre of her being into.

My Beautiful Home is a project that seeks to rekindle the ancient art of decorating and beautifying rural homesteads using materials, colours and pigments gathered from the earth. Prizes are practical and useful: shovels, rainwater tanks, three-legged iron pots, day-old chicks, and even a hive and beekeeping course for regional winners.

But as judging day was nearing, Masuku had spent a sleepless night worrying about what to wear, whether her personal presentation could match the creative effort she had put into her home. Then, she says, a message from amadlozi, the ancestors, had arrived with clarity: “Peggy, go to the forest.”

Careful not to wake her husband and children sleeping on their grass mats, Masuku quietly opened the front door. She took a deep breath, inhaling the scent of the mango flowers, and trudged off into the darkness.

As dawn broke across the rugged granite hills around her valley, Masuku walked, eyes to the ground, searching for seeds from that hardy foliage of Africa – the mopane tree. And lots of them, to stitch into a regal outfit that would make her the talk of the district.

“Everyone is an artist,” says Masuku. “We just need to learn how to see.”

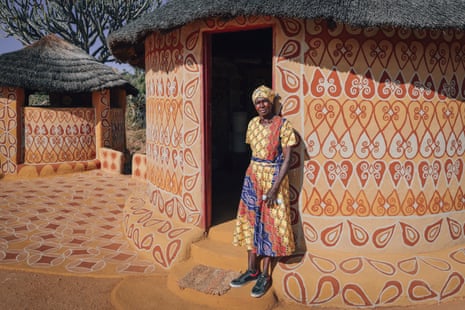

Every autumn, as the morning air gets colder and the final harvest of corn and sorghum is stashed in the rafters of the round clay houses, called rondavels, hundreds of women from across this region begin decorating. With pigments mixed from different muds, and a watery clay solution applied to the walls, it takes about two to three months to complete a small home inside and out.

-

Clockwise from top left: detail of decorative art from Matopos; interior of a rondavel (a round clay house) in the village; the My Beautiful Home contest gets under way; a bicycle, the main form of transport in Matopos, rests against a decorated wall

The process has deep ancestral roots that go back thousands of years. Many art historians believe the foundations of the cubism movement drew on the geometric shapes, motifs and textures used in everyday rituals across Africa. Here in the Matobo Hills in southern Zimbabwe, the connections are clear to see.

At the village prizegiving, the singing, cheers and ululating when every single participant collects a prize reflects the huge love for this annual art tradition, a living testimony of the African philosophy of Ubuntu: “I am because we are.”

Patience Sarif, a local coordinator, says: “The art aside, this competition is all about community spirit – each woman inspires and supports the next. You can see it in their daily lives – . Life is hard. They clean and cook, gather water, plough fields, and yet they still find time to work on beautifying their homes and encouraging one another. It is inspiring to see the joy it creates. It’s also really exciting to see how many more young women are involved. Culture is becoming cool again.”

And it is nature that provides the denouement as well as the inspiration for this art movement. When the summer rains arrive in early November, the beautiful motifs and designs, testimony to hard work and pride, are washed away in a matter of days.

“When that happens I sometimes stand in the rain watching my creation wash away, and I feel sad,” says Masuku. And then she looks up and smiles. “But then we start dreaming about what to do next year.”