Green-Wood Cemetery leads sustainable landscaping

Horticulturists, like theater directors, work behind the scenes. They don’t sign up to get booed. But during the summer of 2019 at Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery, its director of horticulture, Joe Charap, was chewed out by lot owners time and again. His offense? He had decided to stop mowing half of the site’s 400 acres of turf to reduce carbon emissions and check the spread of invasive plants.

“The headstone was shrouded in weeds and covered in tall grass,” one person said of their father’s plot. “It’s disrespecting our family.” Another wrote: “The area looks terrible. It is not mowed and looks disheveled.” And another: “I couldn’t help but feel I was looking onto the Serengeti plains with grassland growing out of control in a manner that I feel desecrates the final resting place of all lying in eternal [sic] slumber. What’s next, controlling the growth with grazing sheep and cattle?”

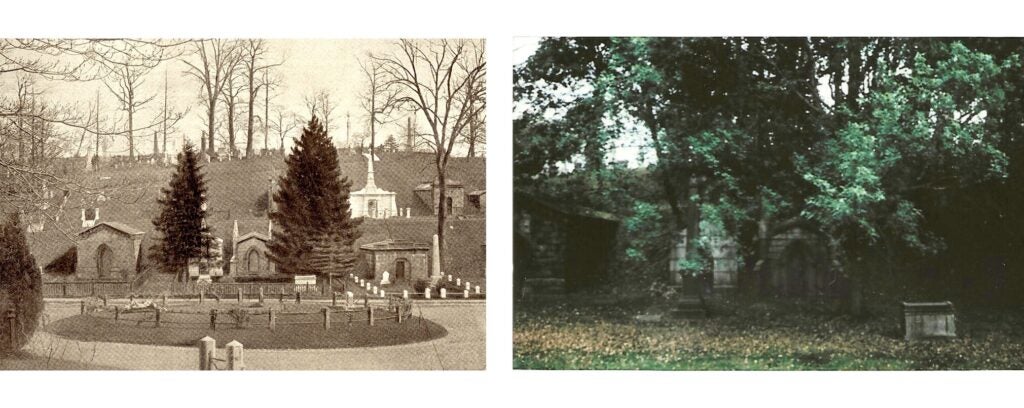

A life-long New Yorker, Charap expected some shock. For a cemetery, not mowing was a radical step, but the complaints still stung. After all, his job was to care for Green-Wood’s most valuable feature: its landscape. The glacier-carved hills, valleys, and ponds were the reason a group of wealthy Brooklynites chose it for one of America’s earliest rural cemeteries in 1838. Since then, New Yorkers of all stripes have visited the roughly 500-acre grounds to mourn, or get their fill of fresh air and nature.

But those grounds, as Charap learned over the first few years in his role, were changing for the worse. The main culprit was Bermudagrass, a fast-growing, warm-season invasive which had been introduced to the southern US, likely from Africa, more than two centuries ago. At Green-Wood, Bermudagrass was growing unabated due to some of the energy-intensive practices used to tend cemeteries and yards across the US.

It was a model that Charap walked into when Green-Wood hired him out of horticulture school in 2015. Rejecting it wasn’t going to be easy. There are upwards of 144,000 cemeteries and graveyards in the US, according to one NASA cartographer; they cover 4,300-plus acres of New York City alone. With all that ground, there’s plenty of room to test out lawncare techniques that break with the century-and-a-half tradition of over-pruning, overwatering, and over-fertilizing open spaces. A strategic, yet laissez-faire approach, as more research is finding, can save resources and help mitigate human impacts on local wildlife and climate change.

To put it more bluntly, by scaling back mowing, Charap wanted to change Americans’ perceptions of landscaping, one cemetery—or tiny burial plot—at a time.

However Bermudagrass ended up at Green-Wood in the 20th century (perhaps from ship ballasts or Southerners who buried it at the gravesite of a loved one), by 2019 it had taken over 10 percent of its grounds, thanks in large part to Brooklyn’s warming seasons.

Aesthetically, the plant was a disaster. Straw-like and brown when dormant, it only turned green after Mother’s Day, an important holiday at any cemetery. The more frequently it was cut, the faster it grew: By mid-summer, it was creeping up over the gravestones by about two inches per week. What’s more, the growing season was reaching into November due to climate change. The result was an intractable monoculture.

As landscaping crews battled the Bermudagrass, Green-Wood’s annual mowing bill ballooned to $1.2 million. The use of herbicides was also proving costly and ineffective.

Charap had once looked at these expenses as one would their utility bill—annoying but unchangeable—until he began assessing the true cost of conventional lawn care. The weedwackers and ride-on mowers burned 12,000 gallons of gasoline a year, equivalent to 235,000 pounds of carbon dioxide emissions. As an accredited arboretum, Green-Wood boasts more than 7,000 trees, but the canopy is well short of the forest it would take to offset such pollution. Decades of weekly mechanical mowing had also left visible scars, like pockmarked monuments and eroded slopes, as well as invisible ones, like the native flora unable to survive the blades.

Charap knew that most lot owners expected cemeteries to be neatly manicured, but he wanted to do better. So he turned to Cornell University’s Frank Rossi, a straight-talking, Bronx-born turfgrass scientist who advises major golf courses and sports teams like the Packers and Yankees. They convinced Green-Wood’s trustees to invest in a three-year partnership with Cornell to tackle the effects of Bermudagrass and climate change on the cemetery’s landscape. If it all went according to plan, Green-Wood would become the leader in this fight among all urban grasslands.

Nobody at the cemetery had studied these effects before. In 2018, Charap and Rossi flew a dozen drone missions over its core to uncover the biggest problem areas. They buried three microclimate sensors in different areas to learn where Bermudagrass was growing fastest, and outfitted 20 mowers with trackers to record their activity and fuel use. The two experts also brought in new seed mixtures and topsoil for landscaping, and laid out more careful burial procedures to keep invasives away from fresh gravesites. But their main hurdle was that Bermudagrass thrives in disturbed soil—an existential crisis for an active cemetery with more than a thousand burials each year.

In June 2019, a fluke in the landscape showed them a way forward. Rossi and two colleagues were walking through a quiet corner called the Hill of Graves when they stumbled on a patch of little bluestem, a well-known native prairie grass, rising out of a spot the mowers had missed. So there was a chance that underdogs could grow here, and maybe even beat out the Bermudagrass. Why not let certain areas go a little wild and see what happened, Rossi asked?

He and Charap decided to try. They removed a hundred acres of Green-Wood from the mowing rotation entirely, and set aside another hundred to be mowed monthly. With that, they charged into a cultural firestorm—and very quickly those comparisons to the Serengeti plains. “We started having this institutional conversation about reimagining the American lawn,” Rossi says. But that conversation became painfully one-sided. Charap, who discoursed with lot owners in person and over email, faced the brunt of it. “We underestimated the emotional connection that many people have with turf,” he says. While some told him they agreed with his mission, they also demanded, “but don’t do it on my lot, do it on that other lot.”

Within two months, a disappointed Charap had all the grass mowed, and he and Rossi returned to the drawing board.

Almost two years later, on an unnervingly warm late-spring morning, Rossi bounds up the gently sloping Hill of Graves with grass lapping at the top of his black leather boots. “Where’s that little bluestem, Joe?” he shouts behind him to Charap, who is not about to give chase in 90-degree heat.

There’s nobody else around. And it’s otherwise quiet save for a mockingbird imitating a car alarm from a dogwood on the hillside. The sweet fragrance of a flowering linden fills the air. The grass hasn’t been cut in three weeks, and what looks like a meadow has grown in. The Hill of Graves, like most of Green-Wood, used to be cropped within two inches of the soil almost every week outside of winter. Now it’s mowed to five inches only six times a year.

“It’s never looked this good, Joe,” Rossi says. “If this is what six mows looks like, we could do this for the whole cemetery.”

That’s Charap’s goal, and after the initial setback of 2019, this is a more carefully plotted step in that direction. Last year, he and Rossi set aside 43 acres of what they’re calling perpetual meadows, and the roughly 12-acre Hill of Graves is the largest one. Still, Charap carries the scars—and lessons—of that earlier summer. “We thought that no one was going to notice when we stopped mowing 100 acres, which in hindsight is just ridiculous,” he says. “You can slowly adapt people to a change in the landscape, but you have to prepare them for it.”

Turf grass is a deeply rooted social construct, Rossi says, pointing to the fact that US households spend around $30 billion annually on landscaping. Most of it is devoted to lawncare, which itself adds to ecological problems. Lawns are considered the most widely irrigated landscape in the country, and the Environmental Protection Agency reports that 5 percent of the country’s air pollution comes from two-stroke mowers. The explosion in lawns has also been connected to a decline in native insects and other wildlife.

But a countermovement is emerging. From suburban yards to historic cemeteries like Green-Wood, there’s a growing push to reckon with the unsustainable consequences of this obsession. “The impact that cemeteries can have by changing the way they’re managing their lawns is significant,” says Sara Evans, Green-Wood’s manager of horticulture operations. Reducing soil disturbances like mowing and digging helps cut down the amount of greenhouse gases released; so does strategic rewilding with meadows and other ground cover.

Indeed, natural grasslands act as major carbon sinks—even more so than trees in places where wildfires are common, given that most of the carbon is stored underground. What’s more, 90 percent of the world’s grasslands have been grazed, cleared, or otherwise corroded, making them one of the most endangered habitats.

Other historic cemeteries are seeing how they can reduce their carbon emissions, too. Cincinnati’s Spring Grove opened seven years after Green-Wood and became the home of the first “lawn plan,” a design that emphasized open spaces and clean lines and was adopted throughout the country. But now, according to Dave Gressley, its director of horticulture, they plant sedge, which requires little mowing, wherever possible, one plug at a time. They’re also working to rebuild their canopy after the loss of hundreds of mature trees to disease and storms. As for meadows, though, Gressley says, “Cincinnati is on the conservative side, so that wouldn’t fly here.”

At Green-Wood, the free-growing patches were chosen in large part by visitation and the contours of the ground. Areas with newer graves were avoided. The Hill of Graves, for instance, is mostly made up of 19th-century public lots. Grass there now reaches halfway up simple flagstones. Fields of clover rise after spring rains, and Green-Wood puts on small classical-music concerts under a sprawling European beech tree at the slope’s crest.

This and the other meadows look unplanned—a little wooly in parts, tidier in others—but Charap and Rossi say they require more attention and foresight than simply mowing. Weed control is still employed twice a year to keep invasives at bay. Instead of a monoculture, Bermudagrass now blends in with native grasses like fescue, bluestem and Kentucky bluegrass. Once on the Hill of Graves, they used a tractor-trailer outfitted with blowtorches to try to regenerate those grasses through fire, as a way to recreate the natural fire cycle that once existed in tallgrass prairies of the Great Plains and upper Midwest. Heating up the soil releases nutrients from decaying plant material that feed the growth of new grasses and flowers. “We’re working with the landscape as opposed to trying to bend it to our will,” Rossi says.

Working with Rossi, who began mowing lawns in New York’s suburbs as a kid and briefly studied to become a Catholic priest, has converted Charap into a turfgrass obsessive. When he began working at Green-Wood, he says, the only thing on his mind was its “charismatic megaflora.” The grass was a place to rest his eyes between trees.

“But now when I look at the landscape,” he says, “all I see is grass.”

Rossi laughs, as Charap continues. “We can plant trees here till the cows come home, but in terms of climate change, that would be a drop in the bucket compared to what we can accomplish with managing the turf better.”

Indeed, Green-Wood has reduced its greenhouse gas emissions by nearly a quarter since 2018. They’ve continued to track environmental data throughout the cemetery—on microclimates, burials, mowing, soil movement—and used that to keep the grass at a taller height, but one that is largely uniform. Rossi and Charap believe that consistency (and the presence of fewer weeds) has led to fewer complaints.

[Related: It’s time to rip up your lawn and replace it with something you won’t need to mow]

Less mowing has created a healthier, often surprising ecosystem. For the first time in memory, Charap and his team found a patch of the delicate pink wildflower springbeauty. A two-year wildlife survey turned up 62 native bee species, most of them in the new meadows. And a male bobolink, a small grassland specialist in decline that migrates between South and North America, recently turned up on the Hill of Graves. During that extraordinary journey, bobolinks seek out weedy fields or tall grass, of which Green-Wood once had very little. In spring, the males look like they’re wearing a backward tuxedo, but their song is their calling card, a robotic, R2D2-like mashup which this one sang from atop wind-blown cedars.

“We call that proof of concept,” Charap says of the discovery.

The third and final year of the Green-Wood and Cornell partnership was a busy one in unexpected and tragic ways. The early months of the COVID-19 pandemic halted all non-burial work. Charap’s eight-person crew of gardeners and arborists assisted with burials, and the restoration staff helped run the crematorium, where workers alternated 16-hour, seven-day shifts. In the pandemic’s first year, almost 5,600 people were cremated, buried, or entombed at Green-Wood—up 38 percent from the previous 12 months.

At the same time, the cemetery offered relief during crisis. As the city went into lockdown, access to greenspace felt like a boon. It was as if Green-Wood, which had been the model for New York’s first parks and was said to rival Niagara Falls as America’s most popular destination, was reborn—a refuge for the living as much as the dead. Roughly 110,000 people came through its four gates in May 2020, almost triple the same month in 2019. The cemetery extended its hours and has continued to keep all those gates open daily. Around 600,000 individuals visited Green-Wood in 2020, up 82 percent from 2019.

For many of these visitors, the meadows became Instagram-worthy favorites. Buoyed by this reception, Green-Wood leaned into them. They turned the lawn in front of its famous Gothic arches into a two-acre meadow. Charap had never seen so many kids playing in it. “This is right in front of the cemetery and we’re saying, ‘This is who we are now.’”

It seems more like a clean break with the past, in which the landscape possesses a voice on par with its many private owners.

Education has become central to their work. Rossi, though technically off the hook at the end of last year, is beginning a new chapter at Green-Wood. He and Charap are planning an Urban Grasslands Institute that will occupy space in a restored, landmarked greenhouse, where they’ll share land-management techniques with climate-change researchers, city parks managers, homeowners—a place to continue rethinking the American lawn.

I met Charap again on a cloudy spring morning in front of his residence at Green-Wood—a brownstone-clad, slate-roofed Gothic Revival gatehouse where he lives with his wife and their two young children—and we walked a short distance to the ridge that marks the southernmost reach of the last glacier in these parts. From there, we looked out upon the flatlands of Brooklyn and the rides of Coney Island along the Atlantic Ocean.

This choice vista had been claimed long ago by Stephen Whitney, the second richest man in New York, when he was laid to rest here in 1860. Whitney wouldn’t recognize the spot now, though; thickset oaks and poplars surround his gabled mausoleum, and seedlings of sweetgum and black cherry sprout from a leaf-strewn understory. In his day, Green-Wood’s official view of nature was benign, then later to be controlled. But never quite as hands off as this. “I have to resist the temptation to make Green-Wood a forest,” Charap said.

As Green-Wood runs out of burial space, Charap’s work is part of its evolution into a cultural institution overflowing with history, art, music, and social events. His goal, he told me, is to help Green-Wood reclaim its origins “as a public garden for the people.” But it seems more like a clean break from the past, in which the landscape now possesses a voice on par with its many private owners.

Below Whitney’s gravesite, Charap brought me to a colony of sassafras trees that had taken over the hillside. He snapped off a branch to expose its aromatic bark, which historically has been used for soaps, teas, root beer, and medicines. Sassafras, with its mitten-shaped leaves, typically moves into forest clearings and old fields—or an unmowed slope in a cemetery reimagining itself as it reaches its 200th birthday. Charap decided to run with this happenstance, so his crew trimmed openings through the flora to allow access to the headstones and tombs. These hardy trees would now attract dozens of butterfly and moth species, and the likes of robins and catbirds would feed on their deep blue berries. Left alone, they will sequester carbon for decades.

“Once you stop mowing, you don’t have to do much land management except for figuring out what’s native and what’s not native and deciding what to keep,” Charap said. “We didn’t choose this. But the landscape can occasionally speak for itself.”