These African heritage sites are under threat from rising seas, but there’s still time to save them

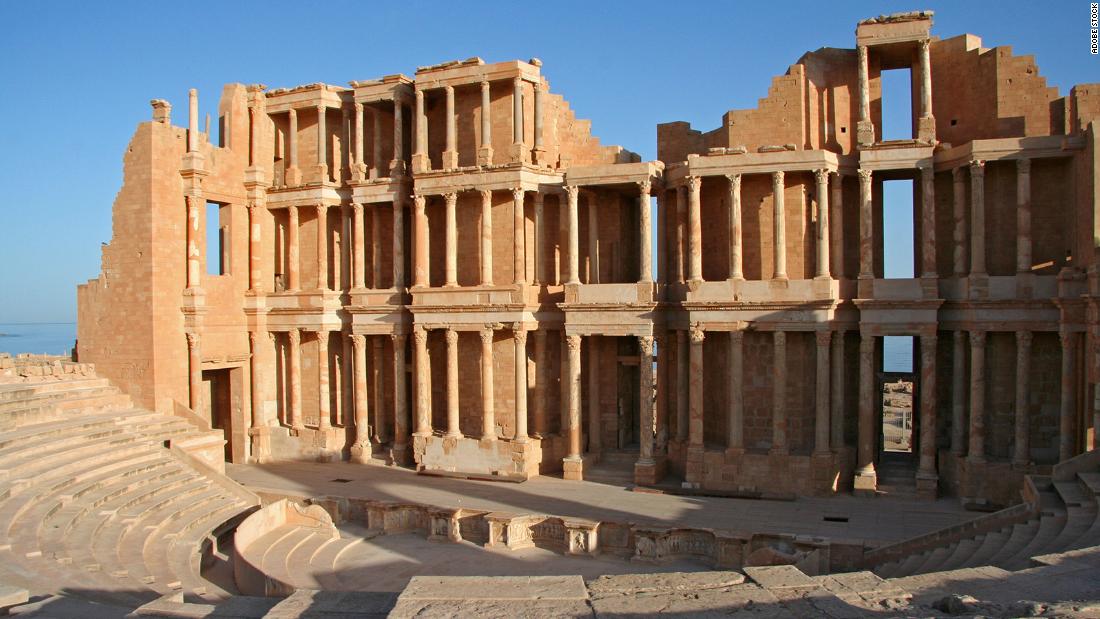

(CNN) — On the shores of North Africa, ancient cities have stood for millennia. The columns of Carthage, in modern-day Tunisia, are a reminder of the once bustling Phoenician and Roman port, and along the coast in what’s now Libya, lie the majestic ruins of Sabratha’s Roman amphitheater close — perhaps too close — to the sea.

Sea levels have been rising at a faster rate over the past three decades compared to the 20th century, the research says, and climate change hazards such as floods, heatwaves and wildfires are becoming more common.

The ancient Roman theater of Sabratha, in modern-day Libya, is one of the sites expected to be in danger by 2050.

PATRICK BAZ/AFP/Getty Images

It found that 56 sites are currently in danger if a “once in a century” flood struck, and that by 2050 — if greenhouse gas emissions continue on their current trajectory — this number could more than triple to 198 sites.

“There is a local value, an international value, an economic value … and an intrinsic value (to these heritage sites),” Nicholas Simpson, an author of the study and postdoctoral research fellow at the African Climate and Development Initiative at the University of Cape Town, tells CNN. “There are some monuments and sites and spaces that we don’t want lost for the next generation.”

Simpson believes the findings serve as an important wake-up call to increase climate adaptation measures and funding across the continent. “There’s an important message of loss and damage from climate change to heritage, which we hope will mobilize greater intent (and) action,” he says.

A first for Africa

In this latest study, Simpson and his colleagues mapped out a total of 284 heritage sites that are recognized or under consideration by the UNESCO World Heritage Centre and the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance, in the 39 countries that comprise the African coast.

From there, the researchers calculated the likely percentage area of the site exposed to a “once-in-a-century” extreme coastal flooding event.

Simpson explains that such an event is an important indicator in understanding future climate risk, because it is these extreme events that are likely to cause severe damage, and climate change is increasing their likelihood and frequency.

“In the 1970s, what used to be a once-in-a-100-year event happened once in 100 years,” he says, “but what we are seeing when climate hazards are amplified … is that a one-in-a-100-year event might be happening once in 10 years going forward.”

Many of North Africa’s ancient cities lie dangerously close to the sea, such as Tipasa in modern-day Algeria.

HOCINE ZAOURAR/AFP via Getty Images

Simpson caveats this, noting that while North Africa has a high number of globally recognized world heritage sites, other parts of Africa may have key sites that are not listed by UNESCO or the Ramsar convention. But he hopes that identifying these world-famous sites might “raise alarm bells for climate risk for heritage in Africa.”

Protecting cultural heritage

The study notes that its findings will help to prioritize at-risk sites and highlight the need for immediate protective action. This could include engineering solutions, such as sea walls and breakwaters, but Simpson warns that flood mitigation measures like these are “incredibly expensive” and there’s no guarantee they can withstand future sea levels.

He adds that in Africa especially, it is crucial to improve local and indigenous governance around the sites and to recognize that the lives of indigenous peoples “are part of the landscape and intimately intertwined with the seasons.”

“Raising awareness about climate risk to heritage speaks to the broader need for greater urgency about [tackling] climate risk to societies,” says Simpson.